Featured Work Archive

15 November 2024

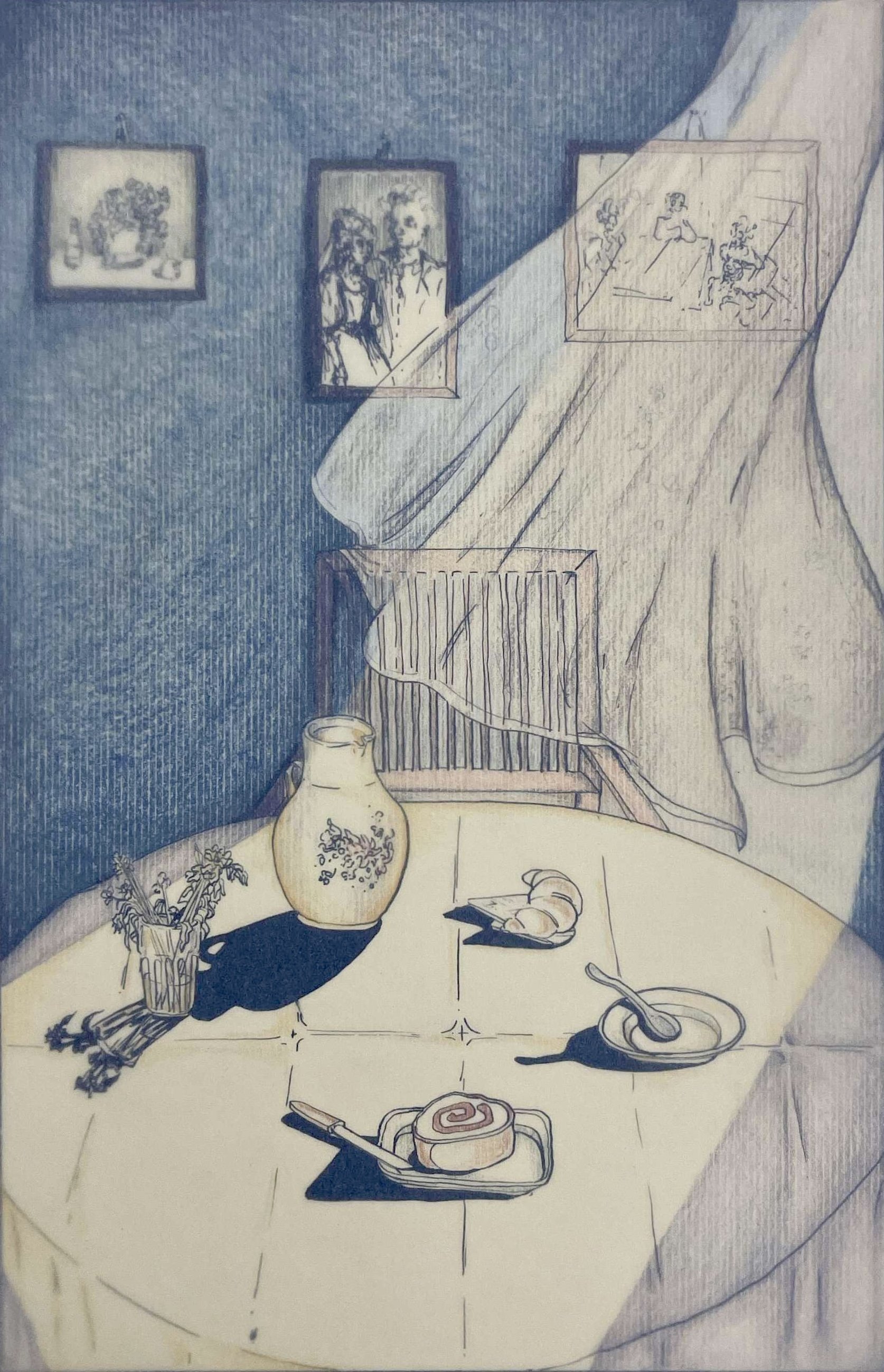

Amalia CastoldiOp. 5

Amalia Castoldi is an Italian painter specialized in oil on canvas, with a distinct focus on surrealistic horror themes. As both a pianist and painter, she doesn’t assign titles to her artworks, preferring to classify them with opus numbers like music pieces. This choice comes from her belief that while her paintings may depict figurative subjects, they transcend mere representation, serving instead as expressions of specific emotions conveyed through shapes and colors. Her secondary production, combined in Opus 6, combines painting with music, where the painting is an exact visual representation of a specific piano piece. Born in Milan (Italy) in 1997, Amalia Castoldi resides and works in her birth city. She has participated in national and international exhibitions, showcasing her distinctive style and thematic approach. With a Bachelor's degree in Piano Performance from Civica Scuola Claudio Abbado (2023; Milan, Italy) Amalia is currently completing a Master's degree at the Conservatory Giuseppe Verdi of Como while pursuing further studies in contemporary music at the Academy of Pinerolo under the guidance of the pianist Emanuele Arciuli. She regularly attends masterclasses with esteemed international pianists like Dorian Britton, Roberto Prosseda and Roberto Plano. Her talents have been recognized with prizes in various competitions, and she has been playing as soloist in classical music festivals across Italy including Piano City Milano, Piano City Trieste, “Flying notes” organized by Fazioli, “Young Talents” in Imperia, “Summer music festival” by Suoni D’Autore. In 2022 Amalia recorded a commercial for DHL and FIAT.

8 November 2024

Meredith MacLeod DavidsonFlammable And Inflammable Have Different Meanings, But Non-Flammable Is An Antonym To Them Both

We felt it numbing in the ovoid synthetic caverns of each of us, bubbling our

fluid. A fuel frenzied, forced phase transition into a state of froth. One of ours,

gripped in the fist of the woman as she shook it at the shopkeeper. Shouting,

I just needed a light, I’ll give it right back! We can feel it lurking about our register

display, the collective discomfort of each customer present, quietly permitting

the altercation to run its course. Neon fringe of a store title leaking through the

windows, sheening green at the woman’s feet. The shopkeeper is hoping the police

will come collect her. That isn’t how this works! He yells from behind his plexiglass

defense. You can’t just come in here and take whatever you want! You can’t. An

insistence. This isn’t how it was supposed to go. Uniformly manufactured, then

packaged neatly in a broad slotted tray for sales. A lighter is an ephemeral thing.

We pass from factory to shop to user to user to user until we inevitably mosaic

beneath tires on tarmac, butane seep and a plastic shattering announcing our end.

An interview with Meredith MacLeod Davidson on finding poetry, POV, and holding an editor position

Tell us a bit about your poetic journey. How long have you been writing? What projects are you working on now?

I’ve always privately written poems (think full teen-cringe), but it wasn’t until undergrad where I started taking it seriously and realized poetry was something I could actually do. I went to Clemson for my undergraduate, and I had the privilege of studying with the excellent poet Cy. Jillian Weise. I took a poetry workshop there, and everything kicked off. I had my first reading in a bar in Clemson, during the Clemson Literary Festival – the same year Natasha Tretheway (then poet laureate) was one of the big poets on the festival lineup. That experience opened up so much possibility for me – I encountered for the first time a world where people were really interested in poetry in the way I was. After college I worked in standard office jobs for about 8 years, where I didn’t get much writing done, though was constantly thinking about it. In 2022 I was laid off from my job. For the first few days I was in a panic – urgently trying to find new work and applying for everything. But then I took stock with myself for a moment. Why shouldn’t I take this opportunity to shift toward a life dedicated to what I was most invested in? For me, that has always been literature, and creative community. At the time I was staying in Merida, Mexico, and I didn’t particularly want to move back to the States. I applied to several programs in the UK and was accepted to the University of Glasgow to pursue a Master’s in Creative Writing. Three months later I hopped on a plane to Scotland and never looked back. Glasgow has been so generative for my practice – not only the Master’s program, but also the greater Glasgow creative community. It is such a spectacular city of artists, creating really subversive, experimental, and earnest work. I completed my grad program in 2023 and since then have been working toward getting a chapbook/pamphlet together, and engaging as much as possible with the creative and literary community in Glasgow. This past spring I got together with another Glasgow-based writer to launch a monthly reading series in the city called crisp packet poetry. We’re now expanding into producing a print anthology and looking toward running workshops in the future too, so I’m really involved in that right now, in tandem with my own projects.

“Flammable And Inflammable…” is told from the perspective of a display of lighters on a shop counter. Did this begin as a persona poem? Can you tell us a bit about the creative process behind this work?

It kind of retroactively became a persona poem, I suppose, but I didn’t necessarily go into it intending that. This came out of a series of pieces in which I was trying to expand my understanding of POV in poetry, and has since fed into some exploration in poems endeavoring away from a species-based (specifically human-based) conception of the climate crisis. In the case of this poem, I imagined this altercation in a shop, then wondered what would happen if it were narrated from the inanimate object which the altercation was over. I was interested by the added layer of tension that occurs when narrated from that position, and had a lot of fun considering the motivations of sentient lighters.

The full title of the poem is “Flammable And Inflammable Have Different Meanings, But Non-Flammable Is An Antonym To Them Both” which is both a true fact and a striking title. How do you typically go about choosing titles for your poems?

This title was very out of character for me – I don’t usually do lengthy titles, if anything, my titles are typically one or two words long. In this poem, I think I chose the factual-statement-lengthy-title approach in part to ground the unrealism of the POV, but also because the apparent discordance between the title and the poem enhanced the added tension introduced by the POV.

You are also the editor of a literary journal. How has being on the other side of submissions affected your own submission and editing process?

I’ve found editorial experience to be absolutely essential to my development as a poet. It makes the emotional element of the submissions process so much more manageable. When I began sending work out to literary journals back in 2019 or so, I took rejection very personally, and would over-edit my work in response to that. Being on the other side of things, you really understand just how arbitrary it is. From the perspective of the editor, there’s a certain threshold of poetic skill (as in, there’s a tangible security and confidence in the writer’s voice, and demonstrates consideration for form, language, and line breaks), that, once accessed, poets should rest fairly assured that they’ve made the longlist for publication. Which, in my experience, is just about every poet dedicated to their craft (and who reads other poets, extensively!). At that point, the pieces that make the cut for publication in any one issue, are chosen purely based on which pieces happen to connect with which editors on whichever day, how pieces speak to other work already selected for the issue, and of course, if there’s a theme, which poems speak best (based on editorial interpretation) to that theme. I once made the case for the inclusion of a poem which didn’t necessarily speak to any of the other editors at the time, but meant a lot to me, because I’d recently read a book which had given me the scientific background to impose a reading on the poem through the lens of that recently acquired knowledge. Had I not just read this book, I might not have recognized that in the poem, and as such, probably would have ended up rejecting it when making final selections. It really is that random sometimes, but it doesn’t mean the piece doesn’t have merit. Sometimes it’s just not reaching the right reader at the right time. This is all a long way of saying poetry is this mutable, ephemeral, bleating thing, and every writer seeking to place work in a literary journal really needs to just keep sending out the radar pulses of submission packets until one of them hits an editor who is ready for it. I have poems which were accepted on first submission, and a poem which took 65+ tries until it surprised me by landing in an absolute dream journal. I see the submission process as a sort of meticulous science at this point, and don’t attach much emotion to it. It’s an administrative task I dedicate a few hours a week to. Approaching it as such helps so that the rejection doesn’t phase me, and the acceptances feel all the more significant.

On the editing side of things, dedicating time to editorial work for literary journals has also given me much more security in my own voice as a writer, and as such, I don’t edit my own work as hastily as I did in my early days of sending work out. When you’re reading through a Submittable queue of thousands of poems, you experience a broad range of work, much of which is wildly inventive and not necessarily the sort of writing you see published all that often. I’m absolutely wowed by that sort of writing and I find it encouraging – it’s made me more excited to experiment with poetry on the page, and feel confident in how those experiments are operating in the poems. In the past I’d be inclined to edit out those experiments to make the poems more palatable for a public audience. These days, I’m more interested in displaying those acts of experimentation and play, and if a publication doesn’t want them, then I still have the creative exercise documented for my own record, and I’m happy with that.

Any advice for emerging poets who are still finding their voice?

Surround yourself with other creatives who are engaged in play and experimentation. Be weird. Lift each other up in community. Make silly publications and throw launch parties for these – even if only your friends show up. Proximity to other writers confident in their unique brand of poetry engenders confidence in your unique brand of poetry. That’s how whole schools of poetics happen. And finally, read!

Meredith MacLeod Davidson is a poet and writer from Virginia, currently based in Scotland, where she earned an MLitt in Creative Writing from the University of Glasgow. Meredith’s has poems in Propel Magazine, Cream City Review, Frozen Sea, and elsewhere, and serves as senior editor for Arboreal Literary Magazine.

1 November 2024

Nancy BellTOMORROWLAND

You are looking into the old photo, leaning across me gruffly and peering down into my lap where I cradle it. Your body has the stillness it gets when you are trying to understand or decipher. I peek at your profile, the outrageous lashes, the angry wound of a fresh piercing from which a nasal hoop sprouts. I’m calmly appalled at this violence. You smell like bread dough.

You grab it from me and fling yourself back on the couch, pressing your thumbs into it and getting a closer look. I tsk at you. I don’t want you to wrinkle it. So rough, always so rough with the things of the world, trusting that anything can be replaced. But I submit to your will. It’s yours. Everything is yours. You are alarming and terrific in your breath and heat and volume. Home again, you seem to rearrange the molecules in the apartment. They buzz like sunshine. You are still somehow a daughter of the golden west, like I said you always would be when we moved to still Ohio. But you barely remember California. Your accent is different than mine.

I’m hoping you will say something when you are done looking—that it was wonderful, that we were wonderful. That it all turned out so well. That it turned out at all. That there is such a thing as turning out. That there is a moment from which one can look back and understand. I’m happy, Mama, I’m well. I’m safe and it’s all because of you. You did it.

*

You break from your stare and toss it aside. I retrieve it as you return to your phone. I tuck it back in the drawer. Why did we open the drawer in the first place, I wonder.

“I told him I’d spend the night at his house before I go back.”

“Oh, good. That’s good. He misses you.”

“It’s just that I’ve stayed here most of the break.”

“Of course. It’s good. I’m glad.”

You pick up your bowl and scrape the last bit out, saying, “Mmmmm. Cimmanim.”

It’s a consolation prize. You know I can’t resist it. There was a time when you got words wrong and I didn’t correct you because it made things seems new, as they were. Cimmanim (on oatmeal.) Aminal (at the zoo.) A day would come, and you were thrilled to share with me the correction: “Did you know that it’s actually cinnamon?” Proud of your expertise, teaching me the right way of things. You held your small index finger to your thumb as you enunciated for me in your motherese: “It’s AN-I-MAL.”

Last day (yesterday.) Next day (tomorrow.)

You take your bowl to the kitchen. Alone on the couch, the photo swims in my consciousness, an afterimage. The Southern California night was soft on our bare arms and legs. The place was just beginning to illuminate into the nighttime version of itself. There was only room for two in the miniature convertibles, which jerked their way to us as we waited, dismissing their former drivers in a line. What color would we get? Which one would you choose?

When we sat down, it was perfect. You drove. Your steering was a charming fiction. You jerked the wheel right and left as the car followed the curving track obediently, but it was real enough for you. It only lasted ten minutes. We could not have covered very much ground. But it was so cleverly arranged, concealing and revealing its scaled and varied vistas. Here, even, was a miniature approximation of a freeway, with a little onramp and then an exit. A tidy journey, entire and optimized.

For my part, I had slipped into a vision I had been carrying without knowing it: how I had assumed adult life would feel. The world would be perfected by science and enriched with the wisdom that adults carried, which would be my wisdom, too. Now here I was, the interpreter of all things. Now, at last, I was a fluent god. And all for you.

The picture is taken from one car back. Must be your father took it, from back there where he rode alone—a third wheel. Or maybe he rode with someone else, a Disneyland straggler or someone’s extra sibling. Your small, black head is set seriously forward, intent on the difficult drive. But my arm lays along the back of the seat and my chin is tilted up into twilight, to the trees parading by and the marble sky.

Nancy Bell is a theatre artist and writer living in St. Louis. She is Associate Professor of Theatre at St. Louis University and works as a director, an actor and and a playwright. Her other work has been published in New Plains Review and The Disappointed Housewife. You can learn more about her work at www.NancyEllenBell.com.

John E. Brady oversees both the narrated pieces for every issue of Passengers Journal, as well as produces each audiobook for Passengers Press. He has been performing for close to four decades all over the world including on Broadway and National Tours, in Film and TV, in industrials, in regional theaters, on cruise ships, in arenas, in amphitheaters, on cruise ships, and as an improvisor. He has been seen and heard in over 100 radio and TV commercials and won several audiobook awards. Favorite role? Dad. Find out more about his work at https://johnebrady.wixsite.com/mysite. He can be reached at audio.passengers@gmail.com.

18 October 2024

Philippe HalaburdaDahmenn Suenno

Born in 1972 in France, Philippe Halaburda is a self-taught abstract painter based in Newburgh, NY, USA. While he holds a degree in Graphic Design from the Academy of Graphic Design and Visual Arts, EDTA SORNAS in Paris, France, his artistic journey transcends traditional education. Inspired by the Bauhaus teaching and elements of the Constructivist technique, Philippe explores the interplay between urban and natural landscapes, delving into their profound impact on human emotions through vibrant and geometric map compositions. Since 2010, Philippe's artwork has adorned numerous European exhibitions, gaining recognition and finding a place in private and public collections. His pivotal solo representation by the Peyton Wright Gallery in 2013 marked his entry into the American art scene, showcasing his readiness to expand his creative footprint. During a four-year stint in New York starting in 2015, Philippe's artistic vision flourished, mainly influenced by the intricate grid of Manhattan. The LionHeart Gallery and Artmora Gallery hosted solo exhibitions in 2016, solidifying his presence in the contemporary art scene. Since 2018, Philippe has collaborated with various European and American galleries and curators, participating in collective exhibitions that have enriched the discourse around his art. In 2021, he ventured into colorful art installations, exploring a new dimension of his work that delves into human psychology. These installations have graced prominent art spaces such as the Hudson Valley MOCA in NY, the Garner Art Center in NY, and Terrain Biennial Newburgh, offering viewers an immersive experience of his evolving artistic exploration.

11 October 2024

Prairie Moon DaltonCarolina In January

If you get hungry enough you’ll eat a rabbit,

but we never did. Instead, she found us

a cold cottonmouth, asked nicely

for its wasted skin. She said we could

split it. Diamond bracelets for both

of us. When Carolina pierced my ears,

she sang. Held a cotton ball to catch

the needle and a pinch of first snow

to numb me. Like a magic trick,

I could not see her hands when she slid

these gems into my head. She is part

of me. Which part? She took her eyes

and left me nothing but her keys

on the table and that day, frozen as this one.

An interview with Prairie Moon Dalton on Appalachia and being a poet of place

How long have you been writing? What projects are you currently working on?

I've loved writing since I was old enough to hold a pencil, but I never took any clear direction. I received some recognition for my poems during high school but didn’t take myself seriously as a writer until later. During my first year of college, I needed a way to work through my homesickness and culture shock. I got off the class waitlist for a poetry workshop and quickly knew it was where I was meant to land. Since then, I’ve had a string of encouraging mentors and peers who ignited and kept the poetry fire burning under me, and I really can’t credit them enough.

Right now, I'm drafting and revising a couple of series that I hope find their way into a first book. One focuses on the historic drowned towns of North Carolina — places purposefully flooded for the creation of reservoirs and dams. The other is a set of poems called "Notices" that use legal jargon to explore the illocutionary silencing of the working poor.

Your bio mentions being an Appalachian poet. This poem feels subtly grounded in that place, particularly with the presence of the cottonmouth. Can you speak to how geography and heritage have influenced your work?

I understand myself as a poet of place, and I seek to illuminate that. I was born and raised in the NC mountains, and I feel lucky to live in this state. North Carolina’s range of nature and culture is incredible. But you can’t talk about the scenery without also talking about the exploitation and consequences that generations upon generations of people have faced. Ivy Brashear puts it well in her essay from Appalachian Reckoning:

“From salt to timber to coal to gas, absentee companies have stripped Appalachia of every resource from which they could make a buck, and left very little wealth behind... Appalachian people have been left to clean up the various economic, social, public health, and environmental messes extraction companies have dumped upon us, leaving very few internal or external resources from which to build.”

Too often are Southern Appalachians misrepresented or neglected in broader cultural narratives, and that drives me to write what I know. When companies leave behind economic and environmental devastation, art is a force of cultural wealth.

“Carolina in January,” a poem about ear piercing and loss, feels almost like a coming-of-age tale. What inspired this poem? Tell us a bit about your writing process.

Hardly do I ever write with one fixed story in mind. Everything I’ve learned, absorbed, and experienced so far in this life curls up inside me and brushes up against itself in surprising ways that I end up writing about. “Carolina in January” in particular arises from one snowy winter, Girl Scout camps, and that annual strange numbness and restlessness of New Year’s Day.

Being a thoughtful observer, listener, and reader is as necessary as writing. I naturally fall into a rhythm of dreaming and active drafting, and I think it's important to take the process as it comes.

You have two poems in this issue, “Carolina in January” and “Flood Event,” a very short piece. Do you envision these poems in conversation with each other? Are there themes which frequently appear and reappear in your work?

There’s a lingering presence left behind by both of these poems. I think the speakers are haunted by similar things - the expectations of their bodies and livelihoods - and they’re both looking for blame or explanation, or both.

What are you reading right now (poetry or otherwise) that you love, or that inspires you?

While we’re on the topic of writers of place, Laura van den Berg is phenomenal. I aspire to her sense of surreality. She renders her home state of Florida in such dazzling ways. I’m reading her new book State of Paradise and I highly recommend her short story collection I Hold A Wolf by The Ears. As for poetry, I’ve been enjoying the wit and wisdom of I Do Everything I’m Told by Megan Fernandes. I return to that sonnet crown all the time.

Prairie Moon Dalton is an Appalachian poet from Western North Carolina. A 2020 Bucknell fellow and Neil Postman award winner, her work has appeared in The Adroit Journal, Rattle, Sprung Formal, The Allegheny Review, and elsewhere. Prairie Moon is currently pursuing her MFA at North Carolina State University.

4 October 2024

Munroe Forbes ShearerThe Five Pillars of Intimacy Direction

Intimacy Directors and Coordinators is an international organization that provides guidelines for the ways in which scenes of intimate relationships or intimate violence (sex, sexual assault, sexual touch, etc.) are conducted in live performance. They frame them in five pillars, listed on a handout that fell out of my journal and onto the adjacent Amtrak seat on my return trip to Boston from New York. I read them quietly to myself.

1. Context:

Before any choreography can be considered, there must first be an understanding of the story and the given circumstances surrounding a scene of intimacy. All parties must be aware of how the scene of intimacy meets the needs of the story and must also understand the story within the intimacy itself. This not only creates a sense of safety, but also eliminates the unexpected and ensures that the intimacy is always in service of the story.

Before I left for New York, Dan and I had only been on four dates. On the first, we met at a bar and he showed me his Grindr nudes folder right there in seat 3A. I tried to cover it with my hand as he shrugged and laughingly told them to enjoy the show. He was wearing a leather harness underneath a plain white t-shirt (He had planned to go to a fetish night if I flaked, which he says that boys in college always seem to.) He has a well-kept beard and a swath of chest hair bursting over the top of his shirt. Despite a gruff exterior, his hands are doll-soft; his voice sensuous and light. He has a series of tattoos of woodland creatures that run up one arm, starting with water creatures (an otter) before moving to ground animals (a chipmunk, a shrew, a bumblebee on a thistle) and ending with a soaring heron at his shoulder. He makes that intense and disquieting eye contact that only bearded blue-eyed psychiatrists in their early thirties seem to be able to, where they stare directly through your head into your innermost thoughts about how badly you want them to rail you in the bathroom at this dive bar. We talked about his psychiatric practice. His interests, his passions, his wife.

He asked about my writing, and my theatre work. My previous relationships. I told him about Sully. I tried to make it seem like it had been longer since we had broken up because I didn’t want it to seem like I was on a rebound (I absolutely was). He told me he was sorry. I found that odd. He didn’t have to be sorry. I didn’t want to be sorry about it, I wouldn’t let myself. We kissed greedily in the parking lot before he paid for my Uber home.

On our second date he came to my house. It was the first time I had a boy over since I left Sully. I dragged him past my squawking housemates and into my closet bedroom at the back of the house where we fucked. Hard. He spanked me until I was on the verge of tears, then slapped me in the face and spit on me (sorry, Mom) before finishing on my chest, cleaning me up with a warm towel, and wrapping me in the warmest and most hospitable grip I could’ve imagined. One hand over my back, sliding tenderly along my bare stomach while the other played music in each tight black curl on my head. He’s not much bigger than I am, and maybe an inch or two shorter, but I never noticed. He makes me feel small, but not diminished. Held, but not squeezed. Pushed, but not used. I made him watch a silly horror movie and he broke one of my wine glasses (which he cleaned up, apologizing the whole time). He had to leave when his wife called, she had locked herself out of their house. I wondered if he texted her to make up an excuse for him to leave. He insists that he didn’t. [MA1]

On our third date we discussed our personal traumas over Cambodian food and had sex in his Honda Pilot.

On our fourth date we canoodled in a corner at an expensive restaurant in Cambridge where we made friends with our waitress. That date was memorable because he came over and we didn’t have sex. The more dating app dates I go on, the more I realize the bizarre rarity of that scenario. We fooled around a little, don’t get me wrong, but he just held me. Long and tender. The intimacy is indescribable. To be held and felt by hands seemingly made for holding and feeling is a pleasure and a pain that’s almost beyond reason. Pleasurable because you feel so safe in that moment, so seen, so removed from the painful choices you’ve made to get there, and finally able to bask in the glow of your freedom. Painful, because after you doze off nose to nose, drunk on each other’s smell, his alarm rings and he has to go home. One of his wife’s boundaries: no sleepovers. That’s reserved for her. The curse of the ethical slut is, after all, ethics. The transition of waking up wrapped in Sully each morning to sitting alone in my underwear with my sheets smelling of Dan’s cologne was painful in a way I didn’t expect. I left Sully the month before to see other people. So why did it hurt so goddamn much?

Then Dan got COVID, so I didn’t see him for a week, and then he had to leave for a psychiatry conference in New York: Tuesday to Sunday. He offered to pay for me to take a train down for the weekend, and I don’t remember anything between that and my butt being in the seat. I knew it probably would hurt. I almost wanted it to. The sexual freedom of non-monogamy requires some masochism—knowing that no matter how much love I felt in his bed, he would send me home with a slap on the ass and a promise to text that he may or may not keep.

2. Communication

There must be open and continuous communication between the intimacy director and the actors. The communication includes but is not limited to: discussion of the scene, understanding of the choreography, continued discussion throughout the rehearsal period, frequent check-ins during the run and an openness to dissent any actions in the process. Avenues for reporting harassment must be made available to the entire ensemble.

On our first night in New York, over a gluten free pizza, he was quiet. I offered a penny for his thoughts. He returned a dollar. He bucked up some courage and asked me how I was feeling about the problematic and tenebrous us. I offered a heavy sigh and shifted back in my seat. Let’s examine my options:

“I think I’m falling in love with you, I hope your wife doesn’t mind.”

“It feels like a knife in the gut every time I look over and see you scrolling on Grindr, even though that’s the reason I’m sitting here as well, and I understand that the established rules of engagement in our connection means that you, in no way, owe me chastity outside of our situationship”

“I really like hanging out with you and want to keep seeing you, but am actively conscious of my inexperience with non-monogamous relationships and what I need out of our connection as a result.”

I settled for the third.

He’s a therapist by trade, so our conversation was almost annoyingly productive. I guided him along some of the walls I was putting up and let him run his fingers over their coarse texture. I told him I was protecting my heart from the pain of occupying the #2 spot in your #1’s life. He said he understood. He asked if I wanted the connection that he and his wife had. I said no. Because I don’t. I’m not ready to be a husband nor a wife, and have no intention of becoming ready anytime soon. It’s why I left Sully. I left Sully to be like Dan, and to be with people like Dan. Right?

I volleyed the question back to him, as is the duty of any good snarky bottom. If I have to express vulnerability at the dinner table the least you can do is offer me a sullen “good?” before changing the subject and footing the bill. Instead, he teared up. He said that he was scared of the idea of me moving away, which I had mentioned earlier. That he could see our connection continuing and blossoming, an ongoing journey of intimacy until I moved on, or he moved on, or both, or neither. I didn’t know what to say to that. I think that I blubbered something about not knowing whether or not he would ever be my boyfriend. In his convoluted answer that I block out most of, he quoted a Hippo Campus song back to me: “I don’t care what we are, it just has to work.” I don’t think men I like should be allowed to listen to music, let alone quote devastating song lyrics back at me. The song is called Understand, which is funny because I don’t. I think that I did care what we were, more than I want to believe.[MA2]

I think I want to be a boyfriend (a wretched word that I deeply and irresponsibly adore), as inane and selfish as that sounds. I left a boyfriend who unreasonably loved every fucking inch of me because I felt like I would explode if I was a boyfriend for another second. Only to sit across the table from Dan and want nothing more in the world than to have him softly kiss me on the head and tell me that he loves me every night before going to bed. And then he did, that night. We left the gluten free pizza restaurant and returned to his hotel, where he pounded my brains out and I dozed off on his chest. Just like I used to do on Sully’s. Every night of our trip he’d kiss me on the head and say “goodnight beautiful boy” before he fell asleep with one arm looped over my ribs. I wish he’d told me that he loved me. He told his wife he loved her every time he hung up the phone. His wife didn’t know I was there. I listened to the phone calls quietly and tried to infer what was going on in her day. Sully used to tell me that he loved me when he hung up the phone.

3. Choreography

Each scene of intimacy must be choreographed, and that choreography will be adhered to for the entire production. Any changes to the choreography must first be approved by the intimacy choreographer.

We spent most of our time in the hotel bed. Not (always) fucking, just existing. In our underwear or naked, always intimately. Touching, kissing, holding, maybe just my feet over his legs or his head sprawled over my lap. Sometimes, if we were deep in conversation, we’d both put our feet up on the wall next to each other like children trying to stay awake at a sleepover and talk about the ways in which people do and don’t exist. Or the ways we wished they did. He’s smart, and knows that I’m smart. [MA3] We have a lot of interests in common, and I would ask him to explain his psychoanalysis to me and he did. It’s kind of easy, in a strange way (at least, when he says it). We get a lot of the same references about culture and society, and true crime. He listens to me when I talk, and I keep up with him when he does. I ask him questions that he answers.

I make him laugh a lot. He told me that he was thinking about shaving his chest and I told him that that would be my own personal Hindenburg disaster. He laughed so hard that he started to cry again, like he did over the gluten free pizza. [MA4] “Oh, the humanity”, indeed.

I like sleeping next to him. He snores a little bit, like Sully used to do. Not a lot, just enough to remind me that he’s there. I slept really well the first night, partially because we split two bottles of Soju at the Korean restaurant he took me to (where they didn’t have any gluten-free options even though he said he checked online, a fact that deeply embarrassed him ((I told him that it was okay, which it was. It takes practice. (((Sully used to call every restaurant to ask about their gluten free options and how serious they were about cross contamination. ((((Just saying))))). The second night I slept less well, but it was okay. I laid there and watched him sleep for a little bit. His beard rustles when he breathes too hard, like a wave ebbing and flowing off a beach. He has a little outcrop of gray hair at the front of his forehead and a few gray drops in his beard. I think he’s insecure about it. I think it’s sexy. He certainly fears getting older (as men in their early thirties do). Sully used to talk about how much he was looking forward to going just a little bit gray, a silver fox-y type of gray. They each have a preoccupation with fixing their hair every time that they look in a mirror.

I can’t help but think of the similarities between them sometimes. Hairy scientists, thirty-ish year old bisexuals, gentle men with sweet pets and gray streaks in their hair. They have hands smaller than you might expect, but both soft and strong. They both like paying for dinner and calling me beautiful.

There are differences, too. Sully’s cat is the love of his life, Dan likes dogs. Dan is kinkier than Sully; Sully was softer to cuddle with. Dan likes soft rock; Sully likes EDM (I like folk.) Dan revels in his non-monogamy; Sully couldn’t handle ours. Dan is married; Sully wanted to be. To me. Dan doesn’t tell me that he loves me, while Sully did on every breath. I know he meant it, too.

4. Consent

Before any scene of intimacy can be addressed, consent must be established between the actors. Permission may be given by a director, script, or choreographer; however, consent can only be given from the person receiving the action. Starting choreography from a place of understanding consent ensures that all parties are clear about to which actions they are consenting, and it provides actors with the agency to remove consent at any time.

Before I continue, I have to get something out of the way: I’m a survivor of sexual assault. I was 17 and he was 21. I stayed with him for two more years. It’s hard but it’s true, and now an inevitable story to get out of the way when engaging in new sexual relationships. It’s important context, I promise. I told Dan at the Korean restaurant, when we returned for his credit card (see: two bottles of soju). I told it in the context of another story so I could[MA5] move on immediately, but he touched me differently after that. He was less grabby and less pushy (not that I had was opposed to the grabby and the pushy, mind you. It looked good on him.) He kissed me before and after he did anything, and asked me softly if it was okay when he wanted to get rough with me. When my mouth was otherwise occupied (we’re all adults here) he put his wrist in my hand and told me to squeeze him if I needed to stop. And I did, and he did. And then he’d kiss me again. Simple, baseline expectations, but I was still overwhelmed by the sundering power of delicate handling to peel back layers and layers of trauma-informed armor and make it possible to feel utterly and radically safe in your body, even if just for a moment.

He can be mean. Never to me, but to others. He’ll make comments about his patients or people walking slowly in the train stations. He’ll say mean things about men we see on Grindr or men that he’s fucked back in Boston. He was rude to a woman working at H&M. It makes me wonder if he’d be mean about me someday, say that I was naive or foolish. If he’d say I didn’t know what I wanted or how to cut my feelings into a shape that fit his. On our first night in New York, he mentioned a guy he used to see and how relieved he was that they never wanted to “buy each other fucking rings,” that they could just have fun and let their relationship be what they wanted it to be in a kind of kaleidoscope, something new on each day. I understand what he meant, it’s what I had signed up for. Though I couldn’t help but feel the presence of a burdensome image of wearing a ring someday, one that he gave to me on one knee. Knowing that he could disparage me with his next conquest for feeling that way puts a knot in my stomach. He’d never admit it, though. Not to me, at least.

On our last night, over a bottle of Montepulciano that I chose and tasted, he asked me to give him the “big feelings” about our relationship like my own therapist used to: what made me happy, what made me sad, what made me scared, and what made me angry.

I told him that the intimacy made me happy, in fact it made me deeply fucking joyous. The tiny kisses in the morning and the ravenous way that he buries his face into me. The conversations about life and death, psychology and responsible artmaking. The way I learn from him and his thoughtful listening to me. We speak the same language about the world, I find.

I told him I was sad that he couldn’t sleep over, that it was hard to feel like our relationship was dictated by his ability to work around his existing relationship and not what we wanted for our lives and our connection. It was sad that the prospect of a life together didn’t exist, even though it was ridiculous to imagine one after knowing each other for barely a month.

I hesitated before I got to scared, but it spilled out of my mouth before I could stop it. I said I was scared that I would fall in love with him. And that he wouldn’t fall in love with me. And that I’d spend my life being bitter that he didn’t, wondering what I could have changed. He asked what would happen if I fell in love with someone else, so that we could revel in our non-monogamous debauchery and indescribable intimacy before going home to other people that love us completely. I know that it’s possible, but it’s hard to accept when that person isn’t around right now. I left that person, remember?

I couldn’t think of something that made me angry. Now I wonder if I’m angry at myself for feeling that way.

5. Closure

At the end of every rehearsal or scene of intimacy, actors are encouraged to develop a closing moment between them to signify the ending of the work. This small moment or simple ritual can be used between takes or runs of the scene, and/or upon the close of rehearsal. We encourage this as a moment to leave our characters, relationships, and actions from the work behind, and walk back into our lives. Likewise, we suggest all parties (including outside eyes) exercise proper self-care during and after the run or filming of intimate projects.

I’m on my way home now, on the 3:00 Amtrak from New York to Boston, train number 88. I managed to find a seat alone near the end of the train. Dan walked me to Penn station, but left me in line. He was quieter than he had been at breakfast, and we sat with my bag between us waiting for my train's gate to be announced. He kissed me before he left, and told me that he was excited to see me back in Boston. He walked away, back out into the sunlight. It was warmer today than it has been the last two, and we went for a long walk in the morning. He checked out of his hotel and his flight doesn’t leave until later tonight, so I think he might go hook up with another guy. I understand. It’s fun. His openness about his sexcapades bothers me less than it did at the beginning of the weekend, knowing that I’m more to him than just another one. I think, at least.

Soon I’ll be back in Boston, where I’ll climb into my unmade double bed and make myself some mac and cheese, do my homework for tomorrow and consider what I want from my life. It’s easy, in some ways: I want to love and be loved with everything I can muster. I want to be agile, to be unburdened, to be unstoppable. To be kind, and have others be kind to me. To have a cat named Pyewacket and for him to fall asleep in my lap. To understand myself, and others. I want to be as thoughtful as I can muster. It’s hard in others, too, though.

If closure is a ritual, consider this mine. Dan can do his on his own time.

Munroe (He/Any) is a queer playwright and essayist from Essex Junction, Vermont, now based in Providence, Rhode Island. His work often centers his rural New England heritage and love of history to explore introspective themes of regret, family, and loss while uncovering intimate truths about human communion. Munroe was the winner of the Rod Parker Playwriting Fellowship Award and the Betsy Carpenter Award for Playwriting at Emerson College, and was a runner-up for the 2023 Tom Howard/John H. Reid Fiction & Essay Contest. During the day, he serves as the fellow for the HowlRound Theatre Commons in Boston, Massachusetts. munroefshearer.com

27 September 2024

Katie Bausler's reading ofLa Gardienne des Sources/The Keeper of the Sources

Written by Kelli Russel Agodon

Katie Bausler is a writer and podcaster. Published written work includes columns, poems and essays in literary magazines, journals and articles in publications including the Alaska Dispatch, Edible Alaska, Stoneboat, Tidal Echoes, Cape, Cirque, and Insider. She also hosts and produces the 49 Writers Active Voice podcast with writers and artists on these pivotal times, writes a newsletter focused on alpine skiing, and is a volunteer public radio DJ and host. She worked as a public media host, reporter and producer and then in marketing specializing in radio spots. Her first work as a professional voiceover artist put her through college in San Francisco. She is working on a collection of essays and poems, working title: Live Like You’re Dying. Katie and her husband Karl live near their children and grandchildren on Douglas Island along a saltwater alpine fjord in Juneau, Alaska’s capital

13 September 2024

Mubanga Kalimamukwentomy mother’s favourite food

but first

my father’s favourite

was fish & chips

a taste acquired in the 2 years he called

Cardiff, home/

fattening his engineering degree.

the potatoes had to be sliced into circles

crisped using my mother’s four step process

/soak the starch out/

/parboil/

/pat dry/

/double fry/

he liked it for breakfast

recovering from those nights he came home angry/

his fists greeting

my mother’s body

he liked it sprinkled

red with crushed chilis

red where his hands had left lacerations

where my mother leaked like a heavy cloud.

eating the sun with her skin/

singing into the fire

my mother recreated this favourite

best at fighting the grog in his voice

the morning after

we bury

my mother

he wakes up ravenous

/he takes his seat/

/unfolds his fists/

/cradles his face/

weeps.

& I never knew my mother’s favourite food

An interview with Mubanga Kalimamukwento on memory, genres, and inspiration

How long have you been writing poetry? What advice would you give to emerging poets?

I am pretty new to poetry. I’ve only been writing it since 2021ish and even then, the push was being in a required poetry class for my MFA, so I am still quite pleasantly surprised by magazine acceptances and consider myself an emerging poet. So some advice to me based on my experience in other genres is that writing is like practising your handwriting: the more you do it, the better you get, and with that, the valley times are shortened and the peaks longer, more frequent––or, hang in there.

Tell us a bit about your work within the literary community. You founded a journal and work with a prison writing workshop. What have those experiences been like?

It all stems from my early experiences as a writer. When I started writing my first novel, the experience was like being inside a drum, talking to myself. My community was with other readers like myself, but it took much longer for me to find my way to other writers. The journal is me trying to make a landing a little softer for other Zambian writers; beyond publishing them, we work very hard to help them build community through our social media engagement, mentorship opportunities and masterclasses. We are only 2 (almost three issues in), but the feedback has been incredible, and working with first-time authors is such a rewarding, necessary experience for me. Being part of the African literary ecosystem for me is about looking around at the tables where are sit and making space for others like me, or others who are at earlier stages in their career, the way I might have wanted a few years ago. I have been very fortunate with literary friends, I have a lot of people who hold me up, and I try to do the same for others. My absolute favourite thing is when writers I teach, mentor or publish win outside of the spaces I curate.

As for my work with the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop, that’s more of a marriage between my legal and writing careers. The additional pleasant surprise has been that I have found teaching writing really enjoyable––to be witness to their growth as artists is an honour.

“My Mother’s Favorite Food” is a heartbreaking exploration of the relationships between father, mother, and daughter. Can you speak a bit on the theme of family, and how it appears in your work?

When you lose your parents young, like I did, most of the time you spend with your parents is in memories, and those can shift and change shape over time. In engaging with the memories of my father, over time, I have grown softer in my perception of those times and of him. But a few months ago, I was making fries for dinner and ended up sharing how I came to this recipe- which was, like with most of my recipes, through observation and quite suddenly, I realised that in all that time I had spent with my mother in the kitchen, we had been making things my father loved and not things she loved, and that broke my heart a little and birthed this poem. What’s happened to me is what happens to many daughters. As your reflection changes, as you see more of your mother in your own face, you gleam a new understanding of things you had never considered before. For me, it was just a pause. I talk so much about my mother, but how much did she reveal? How much of her magic was drowned in the mundane? What would she want me to remember?

You are also a novelist and short story writer. Can you tell us a bit about how the different genres you write in inform each other? What is your creative process like?

In novels, I know going into a project that I have a mountain ahead, and because of that, a lot of the early creation process is really just putting one step in front of the next. With each novel, I have to remind myself that my job in that first draft is just to take the next step–meaning, not looking too far ahead and not turning back. It’s more of a long-term relationship. I know there will be revisions, the necessary culling of darlings, conversations with early readers, editors, my agent, and more writing. But maybe because my entry into creative writing was through the novel, it doesn’t seem daunting.

Short stories pose a greater challenge. I often feel like I am in vertigo, absolutely no idea what is going on until some unpredictable moment when the heart of the story, the voice, the container–all of it, reveal themselves to me. That’s much more taxing on my mind than the novel.

Between those two is poetry, which is a welcome exhale. I write poems only when the image is clear, so it is the most accessible form for me for that reason. Some poems have fought me on this, where it was perfect in my mind and gets convoluted on the page, but My Mother’s Favorite Food wasn’t one of those, it appears now precisely as it came to me while I made dinner.

The greatest gift that writing across genres gifts me is that they bleed into each other; my prose is strengthened by my poetry, and my nonfiction learns everything from my fiction.

What are you reading right now (poetry or otherwise) that you love, or that inspires you?

My life involves a lot of studying right now, so I am absorbing much of my poetry through literary magazines. I loved Adedayo Agarau’s, fine boy writes a poem about anxiety. Every few months, I marvel at Drowning Manifesto by Tala Abu Rahmeh, and I am still reeling from Blessings Over the Bodies of My Father’s Murderers by Rachel Rothenberg. My softest spot is for African writers. I remember how excited my editorial assistant and I were to receive and read Sihle Ntuli’s Kasala (for a first-born twin), which straddles between English and the author’s mother tongue. In my first poems, I decided that I was going to frame poems within Zambian proverbs because my earliest recollections of storytelling at school involved proverbs; as I started writing, I quickly realised that some words did not want to and could not be translated without killing them on the way and so the poem became about those words, those phrases and the different meanings they took in my mind as a polyglot. I always love multilingual poetry. Inspiration-wise, I love singular words. Sometimes the sound of them, sometimes the shape. Recently, I have been working with the word Muzungu- which means white person ( in one sense) but can also sometimes be used to mean someone who has foreign sensibilities. I saw this TikTok video where a creator was pointing out similarities between the word Muzungu (meaning wanderer) and Bantu words for aimless wandering or dizziness. So, words, words inspire me.

Mubanga Kalimamukwento was born in Lusaka, Zambia. She is the winner of the Drue Heinz Literature Prize (2024), selected by Angie Cruz; the Tusculum Review Poetry Chapbook Contest (2022), selected by Carmen Giménez; the Dinaane Debut Fiction Award (2019) & Kalemba Short Story Prize (2019). Her work appears or is forthcoming in Contemporary Verse 2, adda, Overland, Menelique, on Netflix, and elsewhere. She has received support from the Young African Leadership Initiative, the Hubert H. Humphrey (Fulbright) Fellowship, the Hawkinson Scholarship for Peace and Justice, the Africa Institute and the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. Her editorial work can be found in Safundi, Doek! Literary Magazine, Shenandoah and The Water~Stone Review. She founded Ubwali Literary Magazine and co-founded the Idembeka Creative Writing Workshop. When she isn’t writing or editing, she mentors at the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop. Mubanga is a current Miles Morland Scholar and PhD student in the Department of Gender, Women & Sexuality Studies at the University of Minnesota (Twin-Cities), where she is also an Interdisciplinary Center for the Study of Global Change (ICGC) Scholar. Her debut collection of stories, Obligations to the Wounded, is forthcoming from the University of Pittsburgh Press.

John oversees both the narrated pieces for every issue of Passengers Journal, as well as produces each audiobook for Passengers Press. He has been performing for close to four decades all over the world including on Broadway and National Tours, in Film and TV, in industrials, in regional theaters, on cruise ships, in arenas, in amphitheaters, on cruise ships, and as an improvisor. He has been seen and heard in over 100 radio and TV commercials and won several audiobook awards. Favorite role? Dad. Find out more about his work at https://johnebrady.wixsite.com/mysite. He can be reached at audio.passengers@gmail.com.

16 August 2024

Ulysses HillTired Man on Grass BW

Ulysses Hill, a dynamic nineteen-year-old born in Los Angeles and raised in Pasadena, is making waves as a writer and photographer while studying at Dartmouth. His unique blend of Black and Mexican heritage infuses his work with a rich cultural perspective. Ulysses seamlessly navigates diverse literary genres, from crafting romantic short stories to thought-provoking essays, drawing inspiration from Dostoyevsky, Turgenev, and Baldwin. A YoungArts finalist in creative nonfiction, his piece "The Threat of The Black Boy" is featured in the 2023 YoungArts anthology and Active Voice Magazine, alongside contributions to Cathartic Lit and Afritondo. Ulysses Hill's storytelling prowess and versatile approach promise an exciting future in the worlds of literature and photography.

9 August 2024

Melissa TuckeyAfter the Clinic Bombing

Cincinnati, Ohio

I remember the keys in my hand

turning the bolt in the heavy glass door

flipping the lights on quickly

to scan every woken room

checking garbage cans for bombs

inspecting windows

and doors jambs, sill

and frame, listening for what moves beyond

the sound of my breath

the bass notes in my chest—

Flipping on the camera at the front gate,

signing in patients, many

carrying children tugging holding

cajoling—

their faces weighted

as they held the elevator open—

one to another

third floor, the waiting room

to your left

I studied for a math exam—

keeping an eye on the front gate

worried

the wrong someone would slip in –

sign my book—

take the elevator...

Meanwhile Anita Hill

was grilled

by the senate judiciary committee—

9 white men, all of them

older than dirt—

Are you a scorned woman, Ms. Thomas?

An interview with Melissa Tuckey on the role of personal experience in poetry and on being both an activist and a poet

Tell us a bit about your poetic journey. How long have you been writing? What projects are you working on?

I started writing poetry in 8th grade. I had a teacher who encouraged me and fed me poetry books. My plan was to go to college and become a writer, but the path to do that wasn’t clear to me. And I had some mistaken notions, I didn’t want to be influenced by other poets. My ego was fragile, and I wasn’t ready for criticism. After college, I found work as a writer and environmental activist in the military toxics movement working for safe disposal of chemical weapons and after some years of intense work, I found my way back to school for an MA in literature, and then for an MFA, and I’ve been committed to poetry ever since.

My first book Tenuous Chapel came out in 2013, selected by Charles Simic for ABZ Press’s First Book Contest. Ghost Fishing: An Eco-Justice Poetry Anthology, which I edited, came out in 2018. I’m currently working on & sending out my second book of poems, War Edition.

Can you tell us a bit about the events that inspired After the Clinic Bombing? What drew you to this story?

When I was in college in the 1990s, I worked at Planned Parenthood in Cincinnati at the security desk. This was during a time when Operation Rescue was attacking local clinics, trying to shut them down. A few years earlier, the far right had blown up the building. The Clarence Thomas hearings were around the same time. It was a hard time to be female—to realize what little regard the all-white male senators had for Anita Hill, and to see our local clinics under physical attack. The police were on the side of the anti-abortion protesters. The Sheriff personally delivered box lunches to the anti-abortion protesters and thanked them for their service. This poem came to me with the realization of how surreal it was to be a young woman holding that job—I really did have to check for bombs every morning—and of course, current events spark these memories.

This poem broke our hearts because it feels both historical and timeless. When writing about current events, how do you strike this balance?

I wish it weren’t timeless...but I know what you mean. How do I write about something political without it being flat. I think the key for this poem was that I wasn’t writing directly about current events, but about something I had experienced. Having some distance from the events in the poem helped me shape a narrative. Underneath it, I had an urge to say—hey look—this is how we defended ourselves. We have always fought for these rights and we will continue.

Your bios frequently list you as both a poet and activist. Can you speak a bit about the role of poetry in activism, or activism in poetry?

I’ve been an activist most of my life. For me, poetry and activism are inseparable. We become activists out of necessity. We organize readings and build communities and we create journals and poetry presses. Poets are makers of not only poems but communities. We do these things with the few resources we have to keep our arts vital in the world. As Audre Lorde reminds us “Poetry is not a luxury. It is a vital necessity of our existence.”

As a poet, lived experience as activist shapes how I view the world. After ten years of working in the environmental movement, I returned to school to study and write poetry. At the time, there was a strong push back against political poetry. Meanwhile, people would say—write about what you know. But what if what you know is that the world and our experience of it is political?

I was in graduate school when the US wars in Iraq and Afghanistan began and when Sam Hamill put out his famous call for anti-war poems that crashed his web site. Dozens and dozens of readings in opposition to those wars were held across the country. It was an uprising of poetry.

While living in DC, I met Sarah Browning who asked me to serve as coordinator of DC Poets Against the War because she wanted to organize a national poetry festival (which became Split This Rock).We participated in activist events, organized poetry readings, and led poetry contingents at national marches. At one point we had 100 poets marching with poetry on our signs. A strong sense of community came from this work. From there we founded Split This Rock as a national poetry organization lifting socially engaged poetry and poetry of provocation and witness. The call to build this organization was resonant.

Editing Ghost Fishing: An Eco-Justice Poetry Anthology was a similar effort. It was the first poetry anthology to look at connections between social justice and environmental crisis. Of course, having a new book requires all kinds of activism to get it out into the public realm. Among my favorite actions, Kathy Engel, Mark Reed and I collaborated to create an installation with art and poems from the book at street level in the windows of the Tisch Building at NYU.

Keeping poetry alive in our communities requires a kind of activism. Serving as Poet Laureate is a kind of activism. Lately, I’ve been participating in and organizing Poetry for Palestine events.

Poetry and the arts are vital for activist movements. Poetry gives us access to human complexity and imagination. It crosses borders and connects us across cultures; it reclaims language from the marketing executives and politicos, it speaks deeper truths, and it’s not yet been ruined by money or religion. These are all necessary tools for surviving current moment and shifting our culture toward something more life supporting.

What are you reading right now (poetry or otherwise) that you love, or that inspires you?

I recently had the opportunity to hear a conversation between Tracy K. Smith and Roger Reeves that sent me back to their work, I love the complexity and generosity of each of these poets. I’ve also been reading Palestinian poets, Mahmoud Darwish, Ghassam Zaqtan, and Tawfiq Zayyad.

Any advice for emerging poets who are still finding their voice?

Study the craft. Read widely. Be adventurous in your writing and reading. Attend poetry readings. Find your community. Support other poets. Take your own work seriously even when no one else does. Disconnect from social media. Be in the world fully & stay out of debt.

Melissa Tuckey is a poet, editor, and teaching artist who lives in Ithaca, New York. She is author of Tenuous Chapel, which won the first book award at ABZ Press and Ghost Fishing: An Eco-Justice Poetry Anthology published by University of Georgia Press. Her poems have been published at Beloit Poetry Journal, Cincinnati Poetry Review, Missouri Review, Kenyon Review, Witness, and elsewhere. She teaches an online mixed level poetry workshop.

2 August 2024

Lisa HentschkeFatherland

Finn picks up the hitchhiker despite my protests. He thinks I’m too cautious. ‘You think everything in the world is out to get you,’ he says. ‘It’s just a young girl,’ he says. ‘It’s cold out,’ he says. He pulls over.

The girl in question has dark hair and dark eyes and a thankful smile. Finn rolls my window down but spares me the burden of having to talk to her, yelling ‘Get in!’ past my face. I hear the door behind me open and a small voice thanking us. The girl scoots over to sit behind Finn. I glance over my shoulder and catch her eye briefly.

I think of movies like The Hitcher and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. I imagine a pocket knife tucked into her jeans, underneath her shirt. I imagine her caressing it, almost subconsciously, before striking us with it. I’m always waiting for the knife to come out.

‘Where are you headed?’ Finn asks.

‘Just up north,’ the girl says.

‘Ah. Lucky. So are we.’

‘I thought so.’ There’s no hint of a smile in her voice.

‘What’s your name?’

‘Sarah.’

‘I’m Finn.’ He points at me. ‘That’s Conor.’

‘Nice to meet you.’

‘Nice to meet you, too.’

Finn smiles. I try to exchange a look with him but he ignores me. He turns his attention back to the road and I lean my head against the window.

The first snowflakes of the year are falling.

In the corner of my vision I see Finn’s hand move towards the radio. Surely not to turn it on; he always claims he can’t focus on driving with music on. That’s the rule. He drives, no music. I drive, music. Except I never drive.

Finn turns on the radio.

‘I love this song,’ the girl says from the backseat. Finn hums in agreement. I don’t hear a song playing at all.

The roads are unmaintained, full of holes, and my head bangs against the glass painfully, at one point so hard it might bruise. Let it. Finn looks in my direction but now I ignore him. The snow outside sticks to the ground. It doesn’t melt. It lingers.

‘Are you two brothers?’ The girl asks.

I glance at Finn. He’s suppressing a smile. Of course he is; he doesn’t worry about anything, ever. ‘Do we look like brothers?’ he asks.

We don’t. He’s got pale skin and a sharp jaw and red hair, I’m dark and circular. The girl and I could be siblings, though. We’d pass well.

‘Conor’s my boyfriend,’ Finn says.

‘Oh! Oh, God, I’m so sorry.’

‘We get this constantly. Don’t worry.’

‘Oh my god. Still.’ She laughs awkwardly. ‘If it helps, I’ve made this mistake more often. Asking couples if they’re siblings.’

‘I’ve done it the other way around,’ Finn says.

‘You’ve never told me this!’ I exclaim.

‘Ah! He speaks,’ Finn says, turning to me. I hate when he does that. He doesn’t realize how condescending it is. ‘So, I assumed these siblings were a couple. Met up with them a few times and only, like, the fifth time did I find out they were just brother and sister. They had to correct me. I asked about their anniversary.’

‘Hah!’

‘It was awful.’ Finn is grinning, as always, and he mouths something to me that I can’t quite make out. I think it might be I think this is fun, do you? or something but when he sees my confusion and does it again, it looks more like I am going to kill you.

‘It’s snowing,’ the girl then says, her voice filled with almost childlike wonder. It breaks my heart.

‘It is,’ I say.

‘Beautiful.’

‘As the driver, can’t say I agree,’ Finn says.

For a moment we’re all silent, watching the snow.

‘Sorry, what was your name again?’ Finn asks the girl. I can’t believe he doesn’t remember. He’s usually very good with names.

‘Sasha.’

‘Ah.’

Was it?

*

Finn was born on an old farm in the middle of nowhere. Growing up, his friends were the sheep, pigs, and chickens. Elementary school was his first real contact with non-family members and even then he wasn’t too interested. He’d refuse invites to playdates and birthday parties in favour of going home and reading books. Poetry, even. How he turned out to be such an extrovert is a mystery.

I’m paraphrasing. His mother told me all this when I first met Finn’s parents about a year ago. A year. Feels long, doesn’t it? And somehow short, too. Too short. We’ve been together for a little over a year now and it doesn’t represent our relationship well. It feels like we’ve known each other for decades.

Sometimes I think about how we would have been if we’d met and gotten together as teenagers. How would we have changed each other in those developmental years? Would he have been able to get me out of my shell? Would I have experienced all those things everyone always tells you to experience when you’re young? Would I have gone to parties, started drinking alcohol, cheated on him? Or would I have motivated him to continue his studies? I fantasize about all the different people we would have become. Me, the wildcard. Finn, the genius. Me, ending up in rehab. Finn, stuck in a miserable job. Us, breaking up before we’re thirty, before we were even supposed to meet.

The day I met his parents was unplanned. We’d driven all the way over to his childhood home, yes, but his parents were supposed to be away for the weekend. He wanted to pick up some old stuff. I just wanted to see the place.

It wasn’t uncomfortable. It wasn’t. I shook their hands, made the eye-contact, did the talking. It was they who barely knew how to keep up a conversation. And Finn kept correcting them, thinking I wouldn’t be able to understand them unless they spoke perfect English. It was all a bit…well. It went alright.

At one point his mother found me alone in the kitchen. I was feeling awkward and doing their dishes because what else could I do, and she told me she had a miscarriage about eighteen years ago. Finn doesn’t know about it and I’m not supposed to tell. I don’t know why she told me. Maybe because she didn’t know me. Maybe she doesn’t have too many people in her life. It doesn’t seem like she does. If Finn and I had been together since we were teenagers, she wouldn’t have told me.

I wouldn’t have been with Finn as a teenager.

I like to fantasize about the impossible. I know I wouldn’t have liked him enough to get to know him, let alone become friends—all in love—with him back then. I would’ve found him annoying, boring, pretentious yet dumb, and all those things he might have been able to turn me into are the things I hate. I would never have allowed him to turn me into anything other than what I already was, back then. Sometimes I wonder why I’ve allowed it now.

And him…I couldn’t have improved him, either. You can’t soften the edges of a boy who grew up on a farm. You just can’t.

I do love farms, though. I love all animals except birds. I’d hoped to see the sheep and pigs and maybe even cows when I went there, but instead I got a pair of old people and the sight of a group of black birds circling the stalls. ‘A murder,’ Finn told me. ‘A group of crows is called a murder.’ I stayed far away from them.

On the way back Finn told me his parents liked me. I’m not sure what made him think so. I told him I liked them, too.

*

‘You can still go back home,’ Sasha says from the backseat. I turn around.

‘Sorry?’

‘What?’

‘I—you said something.’

Sasha looks at me, frowning. ‘I didn’t say anything.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘Yeah. Sorry?’

‘No, no, okay.’ I turn back. I can’t go home, anyway. Not now.

The world looks pure and unbothered—especially out here, on these secluded roads Finn always insists on taking. The only other sign of life is a crow rising from the snow. I think Sasha should be more scared of us. I think she should be more careful. I don’t know how to say this to her without sounding threatening. I think of a knife tucked into someone's pants, someone’s pockets, hidden behind layers of clothing.

‘What are you going to do, up north?’ I ask. It’s a neutral question; she can answer it however she wants. I don’t want to be invasive.

‘Join the circus.’

‘Oh, wow, that’s—ambitious.’

Finn laughs. ‘She’s joking, Conor.’

‘I—Really?’

Sasha ducks her head and smiles. ‘Sorry, sorry. I didn’t mean to make fun.’

‘Don’t worry, Sasha. He’s a bit slow.’ Seriously. He doesn’t notice he’s doing it.

‘Sam,’ she corrects Finn.

‘Oh, fuck, sorry. I’m bad with names.’

‘What are you doing up north? Anything fun?’

‘Not really,’ Finn says. I think about our destination: a dying childhood home, a place now surely filled with tears, a murder of crows. Not really, indeed.

‘Ah.’

I look back at her one more time. Sam. She’s an older woman with intelligent eyes. She looks like me. Maybe I’ve seen her before, I don’t know.

The road stretches out before us until it disappears into the white of the world. The snow has covered everything by now; all is hidden. You can’t even see where the sky ends and the ground begins; the falling flakes blur the lines between matters. They’re from the clouds, from the sky, from the ground, they’re everywhere, all the time. It makes me uncomfortable. The world should have its boundaries.

‘Conor, look,’ Finn says, softly, not trying to get Sam’s attention. He’s gesturing towards the window. ‘Do you see the old house to the left?’

I don’t see anything. ‘Yes,’ I say.

‘I used to go there almost every day.’

‘What for?’

‘Just…because. The guy that lived there would offer me odd jobs, sometimes.’

‘We have an hour left to go. You didn’t live here, did you?’

‘No, I did. For a while.’

He doesn’t elaborate. I don’t ask.

Sam—or was her name Sandra?—asks us to stop at a gas station because she wants to use the bathroom. ‘God,’ Finn says as we watch her enter the shop. ‘I should have offered. Who knows how long she’s been without a bathroom?’

‘What do you think her deal is?’ I ask him.

‘Her deal?’

‘Yeah. What’s happened to her?’

‘Life, probably.’

I look at her one more time. Her hair, though completely gray, looks full and thick. Her wrinkled face demands respect. She could have been my grandmother, but my grandmother never had that kind of spirit.

She doesn’t come back. We wait for twenty minutes before Finn gets worried enough to go ask about her in the store.

‘They said no woman like her had come in to use the bathroom,’ he says when he sits back down behind the wheel.

‘What?’

‘They said—’

‘Yeah, I heard.’

‘They probably weren’t paying attention. We saw her go in.’

Did we? It’s already escaping my memory. What did she look like again? When I think back to turning towards the backseat, I see myself sitting there.

‘Let’s just wait a few more minutes,’ Finn says. ‘Should I turn the radio off?’

‘Is it even on?’

‘Can’t you hear the music?’

‘Turn it up.’

He does. It sounds like static at first, but then I hear it: there’s a voice in there. Soft. Not quite masculine, not quite feminine; not quite singing; not quite speaking. ‘Are you satisfied? If there’s something you could ask for, what would it be? Between safety and freedom, what would you choose? You’re choosing safety, I can see. You’re a safety kind of guy. If you had the balls to do what was necessary you wouldn’t be sitting here, clutching that—’

‘She’s not coming out,’ Finn says. ‘She must have left.’

‘Probably went back home,’ I say. I turn the radio off.

*

When I lie in bed at night, I dream of a monstrous black bird entering through the window of the bedroom and landing at the foot of my—our—bed. If I were to close the window, the bird would just break through.

First, I notice it by the dipping of the mattress near my feet. A threatening weight. If I look at it, I’ll see it stare, head cocked, black eyes glistening in the dark. It will lean closer and expand its wings a little. But I don’t have to look. I know it’s there. In the last few dreams I’ve found it easier not to look. I just lie there, frigid, sweating, feeling the painful beating of my heart. Waiting for the knife to come out. I know where this is going.

Second, I feel it picking at my feet. Slowly, softly, almost gently, like a parent cleaning its baby. It does not feel comfortable. I tried kicking it the first time, but that did not end well for me. So I lie still, allow it to caress my fragile skin, to place its beak wherever it wants, and it will move up my body. It takes its time getting to my legs, my hands, my arms, my neck, and, finally, my face.

Third, the pain. I can’t help but scream every time. There’s so much blood—always—even if it doesn’t stain the sheets. This isn’t about the sheets. It snaps at my mouth and tears my lips right off of my face. It eats the skin off my nose. It digs into my sockets until it can take a whole eyeball out. It tears at my cheeks. I think it might be trying to get at my brain, but I’m always gone before I can see if it succeeds.

When I wake up, I vividly remember the pain.

‘You should get this checked out, Con,’ Finn has said to me more than once. I told him how I sometimes debate whether to wake him up in those nightmares—even though I know, even within the dream I know, I would only be waking a fake Finn up. A figment of Finn. Random parts of Finn my brain’s glued together that will pretend to be a person. Dream-Finn always sleeps through my screaming.

Sometimes Finn lies with his back to me while I am awake. I’m either afraid to fall asleep or afraid to wake up the next morning, and imagine if I were to lean over him, I’d see his stomach cut open and all his guts spread out over the mattress and the floor. Sometimes I look at him and his space in the bed looks empty in the dark.

*

‘Do you want to stop for lunch?’ Finn asks. I’m happy Sandra is gone, but it’s been silent for a while and it’s a relief to have Finn breaking the tension. I’ve been unable to do it.

‘Do you want to? I’m fine.’

‘I’m fine, too.’

‘Okay.’

‘Is that a hitchhiker?’ Finn asks after a moment.

‘What? Where?’

‘Ahead, in the distance. A silhouette.’ Finn nods his head once.

‘We’re not picking up anybody else.’

‘Okay.’

‘Just don’t hit them.’

‘I won’t.’

Now I see her: a young girl with dark hair and round shapes. She’s holding out her right hand, thumb up. In her other hand is an unfolded pocket knife, the blade reflecting the sun. She looks me right in the eyes. We drive past her.

‘I didn’t think we’d made her feel unsafe,’ Finn says.

‘Who?’

‘Sophie.’

‘Who?’

‘Sophie. The girl we’d picked up.’

‘I’m sure that’s not why she left,’ I say. But what I’m thinking is, I’d get the fuck out of here, too, if I were her. I would’ve never gotten in.

‘She reminded me of you, you know?’

‘She did? How?’

‘She seemed like the kind of person who could make me laugh.’

Where did he get that impression? ‘I could use a laugh,’ I say. ‘Been feeling awful all day.’

‘I know. I can see it on you.’

‘Grumpiness?’

‘Dissatisfaction.’

I wonder what dissatisfaction looks like. On me, it might just look like a regular day. I think it looks like old mattresses and scratches on the wall and freezing phone screens. I sent Finn’s mum a dick pic once, just to see what would happen. I don’t know why I’m thinking of this now. I got a response a full week later. ‘Interesting,’ she wrote.

‘I wrote a poem for tomorrow, you know.’

I look up. ‘You did?’

‘Yeah. Didn’t I tell you?’

‘No. And if you thought I knew, you wouldn’t have felt the need to remind me.’

‘Good point. Do you wanna hear it?’

‘You know it by heart?’

‘Of course. I’m not sure I’ll be able to do it, though, once I’m standing there. It might be too much.’

‘Recite it to me. It might help.’