Volume 1, Issue 2

Prose

work by Taylor Nam, Celia Kim, Mark Hall, and more

Taylor NamHow to Make Fire

I turned ten yesterday, so my Mum made me a cherry chocolate cake. She didn’t burn it or anything. It was good, it was fine, but I told Mum: wow, this is amazing, thank you!

The frosting was the best part, super thick like frosting should be. Mum bought it at the store. She said she got it 50% off regular price, so two good, two amazing things in one day: my birthday and 50%. Mum had crazy eyes whole time she cut the cake and she cried a little, too, and Cole asked her why she was crying. I got a little mad at him, even though it was my birthday. Cole forgets things, like even really big things. He’s little. He is allowed to forget things. That’s what Mum says.

I never forget things. I’m really smart, everyone says so, especially Dad, and I know things. I’ve always known things. Like, last year, when I wasn’t even ten years old yet, I knew The Jungle Book straight the way through, even the songs. I could do all the voices, too, especially King Louie’s:

Bu-ba-do-do-do-be-do.

So I knew the cake was from Sue’s recipe book. Sue was Mum’s friend. She lived really far away, even past the McDonald’s. Sue played on the church kickball team with Mum and she had a dog and she let Cole and I call her “Sue” and not “Miss” or “Missus” anything, which I thought was weird, but I kindof liked it, too. Everyone said that she was dying. Scary, right? Everyone said so. And everyone said she was a great, an amazing cook.

Sue could cook anything from anything. Like, when it got cold, Sue made soup with big fat wormy noodles for potlucks and parties. The soup was a magic bag, full of tricky purple vegetables that she said were roots and sprouts and Mum used to say you really couldn’t have a party without Sue.

Sue was younger than my Mum, but not by much because my Mum is very young. Sue cried when she watched those commercials with the pretty lady singing songs about angels with a bunch of dogs in her lap. She laughed at the other commercials, the ones with fat babies crawling around in diapers and making messes. I liked Sue and I liked Sue’s dog, so I didn’t mind going to visit her every single day, even if it was the longest drive ever. If Dad drove, we stopped at McDonald’s. If Mum drove, we didn’t.

There were always a lot of adults at Sue’s house: nurses, church people like the kickball ladies, and Mr. Jay, Sue’s brother, was there, too. One time, even the preacher was there and he wasn’t even wearing his preacher clothes. He was wearing blue jeans and a t-shirt that said, Jesus Is My Superhero. “You can read?” he said when I told him what it said.

“I’m nine,” I said. It was an almost-truth. I guess that’s the same thing as an almost-lie. I should’ve felt bad for almost-lying to the preacher, but how did he think I couldn’t read? Even Cole could read Sam I Am and I’m way bigger than Cole. So I didn’t feel that bad. Mum lied all the time. The same day I told the preacher I was nine, Mum said, “It’s going to be okay” and that was maybe the biggest lie I’ve ever heard said out loud.

There were lots of snacks at Sue’s house. Roasted seaweed crackers and Cheez-Its and dried up squid legs and loads of candy. No one cooked anything. Everything was in plastic bags or soda cans. Dad gave Cole and I peanut-butter pretzels and jellybeans in plastic cups and told us to go to the basement and play with Sue’s dog. He always said it would a quick visit, only an hour or so. (Another lie. My parents are very good at lying.)

When I would go upstairs to the bathroom, there were always a lot of people in Sue’s kitchen. I’d hear them say things about “late stage” through the bathroom door. When I’d come out of the bathroom, they’d be like, “Hi Tessa, are you and your little brother having fun with the dog?” but I didn’t know them at all. They had eaten the entire box of Cheez-Its by the seventh day. That was really annoying. Grown-ups shouldn’t be allowed to have kid food, but when I told them this, Dad was suddenly behind me and telling me to go downstairs.

Mum liked Sue the most out of everyone, so she always talked really loud over people who said stuff about the “late stage”. Mum was always reading and clicking on her computer. I think she was trying to find something to make Sue better. That’s how much Mum liked her. One day, I found a magazine about Chinese medicine on Mum’s desk. The magazine had a bunch of pictures of grass and flowers, but Mum said that Sue was the wrong kind of Chinese, so none of it would work. Mum forgot to make dinner that day, but that was okay, because Dad got us McDonald’s on the way to Sue’s house, later.

I caught Cole sharing his fries with Sue’s dog. Sometimes I feel like I’m always being the big sister. Cole was six and still so little. Sue’s dog threw up chunky potato pieces later, because, like grown-ups, dogs aren’t supposed to eat kid food. Sue’s dog flopped his ears like, it’s okay, you’re just a baby and then ate his own throw-up which was fucking gross. Mum told me not to say that word. I said it in my head, so it doesn’t count.

Now I’m the king of the swingers, whoaaah the jungle V-I-P.

Last year, at the women’s kickball league championship game, Dad and Cole and me made signs that said SUE # 42 and MOLLY #41. My mum’s name is Molly, but no one calls her that. I call her Mum and Cole calls her Mummy and Dad calls her Molls and Sue calls her Sis, even though they aren’t actually sisters. I only have one name. But Cole used to call me ‘Essa, when he couldn’t do T’s.

The game took forever, so Sue’s dog and Cole and I played in the grass behind. We played hunters and we were right about to catch Sue’s dog, but then Cole stepped on a snail, crushing its shell. Cole started crying, saying he had killed the snail’s house. Cole’s more baby than kid so he didn’t mean to. Cry, I mean. Sue’s dog ate the crushed snail and I told Cole that the snail had gone to heaven. It’s what Mum would’ve said. Sue’s dog licked up Cole’s face and you couldn’t even tell that he had cried at all. We laid down on either side of Sue’s dog, Cole and I. He was a good dog, maybe even amazing. Fat-ish, mostly yellow, smelled like dirt, especially around his stomach.

Then Sue and Mum’s team won the championship. They screamed–happy screams like people who had never been that happy ever– and flapped their arms around each other and jumped around with their poochy parts jumping around in opposite directions. I wondered if I would be poochy when I got old, too, although Sue and Mum really weren’t very old. Dad kissed Mum on the mouth, Sue kissed Cole and me, but not on the mouth, and Sue’s dog barked and barked and barked until Cole and I chased him around the bases.

Dad took us to Applebees that night. Sue’s dog couldn’t come with us, because he was a dog. It was a really, really good dinner. Probably the best dinner I’ve ever had, because Mum didn’t make me get broccoli with my pasta. Mum ordered dessert, which was not on her diet, and she said calories don’t count when you’re a champion.

Cole fell asleep in Sue’s lap so she couldn’t reach her ice cream. Sue wiggled her eyebrows at me. They were painted on, or tattooed, with some kind of ink that had turned purple. “Want my ice cream? You’re a growing gal. You need it more than me.”

“Mum says I won’t ever wear a sleeveless dress,” I said. I had heard her say to Dad one day. They talked in the car a lot. I pretended not to listen, because that is what you’re supposed to do.

Sue patted my face. It was very nice. “Nobody likes those kinds of dresses anyway.”

I’ve reached the top and had to stop. And that’s what botherin’ me.

We were always driving to Sue’s house, even before she got sick. Mum went back to work when Dad lost his job. Mum was the smallest bit mad at him for it. I know because I know Mum and I heard their secret car conversations and she always sounded the smallest bit mad. Even though Dad eventually got another job, Mum kept working too. So that left Cole and I without anyone except Sue. We took lots of walks around the lake with her dog.

Sue had about ten million bowls and lots of spoons and her hair bunched around her face when she cooked. She made lots of things, even when there wasn’t a party: red bean buns that puffed when you touched the tops, some kind of rice porridge smashed up with spam and onions, and, my favorite, burnt sugar moon cookies. Sue made the moon cookies into fish shapes, mostly, because she said fish were good luck and it was a shame that our nasty frozen, nasty swampy lake didn’t have any fish.

When I told Mum about the fish and how maybe if there were fish in the lake, then we would be lucky enough to get Sue better, Mum said that was a nice thing to think about. Then she forgot to make dinner again, Dad came home and we got in the car to go to Sue’s house.

I’m tired of monkeyin’ around!

We went to see Sue every day that whole summer. On the tenth day, Cole found the TV remote in the couch and pushed the buttons until the TV bounced awake. Cole didn’t know better. The Jungle Book was already in the player so we watched it twice that day.

There were a lot of things different, now. Kickball had been over for a long time. It felt like forever since we went to Applebees or the mall or the grocery store or anywhere except to Sue’s house. We skipped a lot of things. We skipped church. Dad had a job and Mum still had her job, but they skipped. Cole and I skipped art camp most days. Mum said we’d make it up later. We drove through Montgomery County every day and it was the longest drive ever.

It got really hot. The lake got sludgy and muddy and the wind smelled weird if we drove by it with the windows down. I thought about walking along the lake and catching a fish for Sue, if fish even lived there, which they didn’t. I thought about walking along the lake with Sue. I thought about walking, somewhere, anywhere, really.

Cole and I played hunters with Sue’s dog and we made forts with the leather couch cushions. Cole cried when he was tired, because he was more baby than kid, and I’d have to make him stop crying. We watched The Jungle Book a lot, probably close to a bazillion times. Cole would just fall asleep on the leather couch cushions or on Sue’s dog. I guess I would fall asleep too, sometimes. Dad would carry Cole out to the car, but I walked myself.

Mum and Dad never talked much on the way home, because it was a really long drive to talk the whole way there and the whole way back. So Mum just cried, but she didn’t make any noise. Her shoulders moved against the back of her seat, that’s how I knew she was crying. Dad kept both his hands on the steering wheel. He didn’t say anything or cry or anything.

I was only scared one time in my entire life. I’m really brave. I’m really big and brave and smart and I’m not usually scared.

When Sue and Mum won their championship game and they were yelling and bouncing and screaming like happy people, Sue pulled off her cap. She threw it into the air, and her hair came away with it. I mean, it got stuck in the Velcro on the back of the cap, so it just came off. A whole chunk of it. Sue looked at me and then at the hair and then at me again. “Oh shit, she said, “my head doesn’t like hair anymore. Oh shit.”

That’s it. That’s what she said.

Now, don’t try to kid me. I’ll make a deal with you.

So, Sue had this one big-huge painting in the living room. It was big-huge. Like, not big and not huge, but both: big-huge. And, it wasn’t a real painting, just a lot of red, yellow, and orange brush strokes in thick paint. It was like someone melted Starbursts, a lot of Starbursts. Every time I saw it on the way to the basement, I tried to figure it out and later, when I was falling asleep or even blinking, it would appear on the backs of my eyelids. It still does that sometimes.

On the forty-first day, it was all normal, except that the kitchen smelled like Cheez-It’s and flowers instead of noodle soup and moon cookies. Sue’s brother, Mr. Jay, had a weak faith in Chinese medicine, Mum said. I said but I thought Sue was the wrong kind of Chinese. Mum said, shhh, be good. Dad asked me if I wanted to see her. Mr. Jay nodded at Dad and Mum and me and stirred a mug with flower tea. I followed Mr. Jay upstairs. Cole sat on the steps with Sue’s dog and didn’t even ask to come with us.

Sue did not look right, but I guess I should have known that. She was the same color as her bed sheets and I had never seen bed sheets that color—grayish and yellowish, like her dog’s throw-up after he ate Cole’s fries. I won’t lie: I really hated, I fucking hated looking at her, she looked so bad.

And the room smelled bad, really bad, too. Mum told Sue about art camp, that I had made a watercolor painting and a painting with fruit juices and how my fish looked almost real. I felt funny hearing Mum talk like that. Not funny. That’s the wrong word. It felt amazing, but amazing in a bad way. I keep saying things are bad, because I don’t know how else to say them. The preacher was there, wearing his Jesus Is My Superhero shirt again, and his face had pulled down on the edges. Mum squeezed my hand. A mushy tissue nestled between her fingers and I thought about the laundry piled up, how I had to wear my sneakers without socks for days now. I decided to tell her later that it was okay and that I know she didn’t mean it. Mr. Jay drank the flower tea he had made for Sue. Or maybe he hadn’t made it for Sue. Maybe his weak faith had given out or maybe he didn’t believe in Chinese medicine at all, which would be right, because Sue was the wrong kind of Chinese, but how could there be a wrong kind of person who just wants to get better? The nurse was everywhere, saying that Sue had to take her pills and drink water and roll over so she didn’t get bedsores. Dad sighed into the air above my head, and no one heard it except me. Mr. Jay cried silently into his tea, which didn’t help anyone. Mum squeezed my hand harder, the tissue pressing into my hand lines. Somewhere, below us, outside us, maybe even around us, the bad smelling air turned glue-y, the pasty kind for building bookshelves. It really smelled so bad. I thought about really bad messes, like that one time Cole spilled milk and flour when we were making cookies. Not moon cookies. Just regular chocolate chip ones. Sue’s dog ate the milk and flour goop off the floor. He eats everything. Sue didn’t even get mad, she just popped open the chocolate chip bag and we ate the whole thing–me and Sue and Cole and when Mum came to pick us up, she said we all had crazy eyes.

I stood by Sue’s bed for a long time. Then, Dad made me pray for her and I do not remember what I prayed. Mr. Jay cried. Mum said I did a good job. There were too many people in the room, everyone breathing in glued up air above my head. It wasn’t okay that we were just looking at her die like that, but Mum said, shhh, be good Tessa. Then I patted Sue’s face and the nurse gasped because I hadn’t washed my hands and I said, “Amen stupid shit late stage fucking cancer,” and then I left.

But I don’t know how to make fire.

Cole was still on the stairs with Sue’s dog. Cole said, “I want to see her, too. I’m big enough.” I patted his face. We took the cushions off the basement couch and jumped on them until they got squishy and then we watched The Jungle Book. Cole sat next to me and Sue’s dog sat next to him. He listened to me say the lines and do the voices. Cole was barely a kid, still more like a baby, so I didn’t mind that he fell asleep on my arm.

Break it down boys, break it down boys, break it down

Break it down boys, break it down boys, break it down

Mr. Jay was a nice man, even if he did drink the tea that was supposed to be for Sue. A sad, nice man. We saw him at the memorial service and he didn’t say much. Mum said some stuff at the memorial service, about how she and Sue were best friends, more like sisters, and how she had taken care of us when we had no one else. And I didn’t even know this but Sue actually got Mum her job when Dad lost his. Mum cried a lot and I think Dad did, too. It was a crowded memorial service, lots of people, and lots of food afterwards. I asked Dad why everyone brought food and he said that sometimes eating makes sad people feel better. I said that was fucking stupid and he didn’t slap me like Mum had slapped me the last time I said those words. He just kindof cleared his throat and nodded three times. We ate the food. It was mostly noodles, as if people thought they could make noodles like Sue.

After the memorial service, Mr. Jay was standing by a table that had a picture of Sue when she was a baby. There were a couple vases of flowers, too, orchids and sunflowers and baby’s breath. Mum said those were Sue’s favorites, even if they did look funny together.

I pretended to look at the pictures when I said, “Don’t worry, they’re not amazing, they’re not even good.” I said it real secretively, so no one else would hear me and get offended.

“Oh?” Mr. Jay’s words said, above my head. It was like his words and his voice were not together. His words said “Oh?”, but his voice did not say anything.

“The noodles,” I said, “I tried them. They’re not good. Hers are way better.” I thought this might make him feel better even though we both knew it was over and we would never walk around the lake again. Sue and me, I mean.

Later, Dad took us to give Mr. Jay the leftovers from the party. It felt different walking up the stairs to the Sue’s door. Mum had to work, so it was just Cole and Dad and me. Mr. Jay invited us inside and I saw that big-huge-Starburst-red-yellow-orange painting in the hallway. A sunset, maybe. Or a flower. Or the inside of a person’s blood, maybe. Something like the inside of something, I knew that much.

Dad told Cole and me to thank Mr. Jay for letting us come over and watch stuff on his TV. It was his TV now, I guess. I said thanks and Cole said thanks. Cole said he should get more movies. I said that we really did like The Jungle Book. Cole said, yeah we did, but you could try other movies sometime, too. I said, yeah, you could, maybe movies about girls and not just boys. Dad said we had to go.

Before we left, Mr. Jay said some stuff about how much Sue loved us, Cole and me, and that she would be watching us from heaven. I said I knew that, I knew she was in heaven. Then Mr. Jay said that I was very good at praying. He said I shouldn’t feel bad that it hadn’t worked to make Sue better. So now I knew the difference. Between good and amazing, I mean. Amazing works.

So give me the secret, clue me what to do.

I turned nine. So Sue had been gone for a long, long, time. Like, almost whole year. We had gone to lots of parties without her and they weren’t great (not even close to amazing), because how could you even have a party without noodles or burnt sugar moon cookies or Sue.

Dad was out of a job again so Mum left us at home with him when she went to work. Dad took us to the arcade. We couldn’t bring Sue’s dog, because he was a dog. Turns out, dogs aren’t allowed in Applebees or in arcades, which seems kindof unfair. It should be one or the other. Dad bought a newspaper and gave us the change to play games. We watched other kids ice skating until Dad finished reading the paper. He bought us hot chocolate from the YMCA Kids Club even though he said he didn’t believe in the YMCA. I wondered what Sue’s hot chocolate would taste like, if she made hot chocolate.

Because it had been a year since Sue died, Mum and the church kickball ladies pooled together some of their money and rented a condo at Myrtle Beach. They were going to do it every year in her honor, get the whole team together. When she got home, Mum told me that they walked a lot and talked a lot and they remembered Sue, told stories, that sort of thing.

Later, I heard Mum tell Dad that the trip was the worst ever. She said she kept crying herself to sleep, that she is always crying herself to sleep, and why, why why? Dad said, “I know” and he hugged her, which didn’t seem like enough, especially because Dad would have to tell her that Mr. Jay was dead. They found him two days ago, the day Mum left for the beach. Mum would cry again, drip down her face and hands, and Dad would not cry, at least not very much.

I went out to the backyard. Cole and Sue’s dog were looking for worms. I had told them that I would ask Dad to take us fishing. Maybe the best fish live in nasty lakes, the luckiest fish, the fish that get made into fish-shaped mooncakes. I thought about everything, which is really hard. It’s really hard. Even for someone who is really smart and knows a lot like I know a lot, it is really hard to think of everything. It is really hard to be big enough for Cole and me both, even when you’re really smart like me. It doesn’t matter how many things you know or whether you’re nine or ten or a baby or a gazillion years old, because some things don’t work out and some things just aren’t lucky or amazing at all.

Taylor Nam is an optimist and a doer. She never leaves the house without a book. In the late afternoon, she can most often be spotted running through the park with her dog, Leo, or drinking a glass of pink wine. This is her first literary magazine publication.

Alex AtkinsonWhat Happened at the Barber Shop

1

He was being good, that was the hell of it. He was actually cooperating, for once. He hadn’t screamed, hadn’t cried, hadn’t tried to stay in the car. Off the top of her head, Erica could only think of one other occasion when the kid had just let it happen – and that time he’d been half asleep. Cohen hated haircuts. He said they hurt.

“They don’t hurt, buddy.”

The kid nodded, but you could see he didn’t believe it.

“They feel good.” A bit of a stretch, but…

“Okay.” I’ll eat the poison, mommy. If you say so.

“You wanna see mom get a haircut first?”

“No.”

Erica didn’t know what else to say, so she repeated: “They don’t hurt, buddy.”

“Okay.” Head down, accepting it. It was out of character for the kid – Cohen usually dug in, and wore you out. Fought for every inch of ground, even when it was clear that he wasn’t sure what he was fighting for. Difficult, that was what her husband called him. Strong-willed, the doctors put in all his charts. A bit of an asshole, Erica sometimes joked, which always earned her a look from any other mothers in earshot. It hurt a little to see the kid so broken. So civilized.

Erica had been talking to the kid in the rearview mirror, now she popped out of the car, and opened Cohen’s door with a flourish. “Come on – it’s gonna be fin.”

“Fun,” Cohen laughed. He was new to words.

“Yeah? What did I say?”

“Fin.”

“Nooo. A fin is on a fish.”

“You said fin!” Cohen squealed – too loud, and too delighted for the parking lot.

Erica put a finger to her lips, smiling. “Are you sure?”

“YES!”

“Aw, man, ya got me. Oh well. Come on then. Unbuckle. Let’s go get this done.”

2

“I think about it every day,” Erica said. “A hundred times a day. How ‘bout you? The sound of that bell. Do you remember that bell? When you opened the door… I do.”

3

A bell went off when they opened the door, and a stylist poked her head around the corner. It was one they’d had last time, who had been so good with Cohen, and Erica allowed herself to hope that they would get her again. “Hey there! We’ll be with you in a sec. Sign in on the computer, if you haven’t already checked in online.”

“We did,” Erica said. She had learned her lesson the first time they had come here. Walk-ins were welcome, and maybe even encouraged; but waiting thirty minutes for a haircut – or fifteen, or five – with a restless toddler, who didn’t want to be there anyway, was something that Erica only wanted to experience once. “We checked in earlier, and the thing said it was time. So, here we are. This is Cohen.”

“Hey Cohen!” the stylist exclaimed as if she didn’t remember him at all. Cohen clutched Erica’s arm, and only stared at the woman; but the stylist went on undeterred: “Grab yourself a lollipop, kiddo, and have a seat over there,” she said, and then disappeared back behind the partition. “We’ve got you coming right up.”

Still a wait, Erica thought. No way around it, I guess. It shouldn’t be that long, though. At least, it hadn’t been that long last time. “You want a lollipop, bud?”

Cohen shook his head.

“Okay then…” Erica led her son to the row of the folding chairs lined up against the wall, Cohen dragging his feet the whole way like they were chained together, heavy and awkward.

Like he knew.

4

“Like he knew,” Erica said.

5

They had barely touched their asses to the flimsy cushions on the chairs, when a man’s voice came from the other side of the partition: “Ready for Cohen.”

Good, Erica thought. “Come on, bud, let’s go get this over with.” She inwardly winced at this framing of it. She had to stop making it sound like this was some kind of horror the kid had to endure, instead of normal grooming which was entirely painless. It could even be fun. “Hey, you want me to tell him to give you a mohawk?”

“No.” The kid had no idea what a mohawk was.

“How ‘bout a faux-hawk?”

“No.”

“How about a mustard?”

“Mustard is yellow,” the kid said to his shoes.

“Mustard is yellow,” Erica confirmed. “Come on, let’s get those feet on the floor, kid, whaddaya say?”

“Okay,” Cohen said. So unlike him, he actually did it.

6

“My first thought when I saw you was—”

7

Uh oh. I think Cohen can take him. She would send that to her husband as a caption, if she could sneak a picture. He would laugh. He would worry.

Is he being bad, he would ask, meaning Cohen.

No, he’s being perfect. That was how she would have described it.

Two stalls over from where the stylist they’d had last time was finishing up with another customer, stood a man who looked like he had crawled, starving, out of a 1950’s time capsule. He was about 5’4”, and rail thin. The kind of thin which almost had to be the result of sudden illness. Head too big, shoulders too broad. He wore a short-sleeve, white button-down over institutional slacks, and black no-slip shoes; breast pocket stuffed with combs, and what could only be a pack of cigarettes. He kept his hair high and tight, but longer on top – and this was slicked hard to one side with Brylcreem, or whatever the cool kids were using these days. He waited for them to cross the room with all the dignity of a butcher. Slouched, not looking at them. Just a man there to do a job. He took no joy in it.

When he turned to look at them, his eyes—

8

“I don’t give a shit what he was on,” she said. “If he was on anything… I’m sorry.”

9

—were hard, little marbles set too deep into his cheeks. They darted over her and Cohen as they approached, and then resumed an intense study of his workstation: scissors, and hair dryers, those magic jars of blue.

He didn’t speak, even though they were only four paces away.

Cohen’s grip tightened on her arm again, and the kid missed a step. Here it comes… A familiar little flutter. The PTSD of mothers who have difficult boys. She knew what was going to happen next. Hadn’t she known? She knew. No way around it. Every time. He’s gonna scream. He’s gonna fight. He’s gonna embarrass the shit out of me, and make me look like a terrible mother. And at the end of it all, they wouldn’t even get a haircut. Not from this guy. This guy looked like the type, she had seen it before, who would just stare at them, and shrug.

What the hell do you want me to do, lady?

Take charge, you fucking idiot, Erica would want to say. He’s not afraid of me, but he’s afraid of you. He’ll do what you say. Just try. No one got it. No one understood. No one but the mothers of other difficult boys—

But Cohen wasn’t fighting. He was coming along, just slower than before.

“You okay, bud?” Erica whispered.

“I don’t want it.”

“Want what? A haircut?”

“Uh huh.”

“But we’re already here. It’s our turn.”

Cohen shrugged. What did he care? He was just a kid. If there was any awkwardness, it wouldn’t be on him to smooth it out. That would fall to her. And probably to her pocketbook, as well. She would have to tip the guy, graciously, for doing nothing. She wondered if it wouldn’t be rude to wait until the woman who had helped them last time – who had been so good with Cohen, so firm, yet understanding, even though Cohen had, frankly, been a nightmare – finished up with her other customer, and decided it probably would be.

“Come on…” Erica said. “Mom will be right here.”

“I wanna go home.”

“No.”

10

“Go. That’s what I want to scream at me. Go. Grab that fucking kid, and run, you stupid bitch. Go home. I’m sorry to curse… You stupid, fucking, dumbass b—”

11

“Hop up in the chair, kid.” Flat. Robotic.

How ‘bout a little charm, pal, whaddaya say? “This is Cohen,” Erica said out loud. See? This is how it’s done. She introduced herself, as well; and offered him her hand for a shake. How do ya do, and all that good shit. Come on, dude, don’t mess this up – he’s BEING SO GOOD. Just go along with it. It occurred to her as the guy flapped her arm up and down exactly twice – staring at it the whole time like he was trying to count the hairs on her forearm – that she had a kind of hostage mentality when it came to Cohen. Desperate yet accommodating. Murderously impatient with people who didn’t get with the program right away. He had a gun to her back, and that gun was his willingness to flip completely the fuck out at any time, under any circumstances, excepting all considerations, with little, or absolutely no notice.

She wondered if all mothers of difficult boys were like that.

“You want to say hello?” she asked Cohen, a risk.

“I want to go home,” he pleaded. He spoke too low for her to catch all of it, even bent down as she was, close to his face. “Hurt me.”

“No, buddy. It won’t. I promise. Hop up in the chair, huh?”

“Get in the chair,” the barber said, a littler sterner this time.

12

“I should have left right then.”

13

But she thought, maybe, the guy was just trying to assert his authority. And maybe that was a good thing. A little awkward. No bedside manner on this dude. She imagined there weren’t many customers who requested him for the conversation. But maybe it could work. Something about a man’s stern voice, it got the kid moving in a way hers couldn’t. And maybe he was just hungry, this man, this barber. Maybe that was what his attitude was about. Erica got like that sometimes, too, when her blood sugar was low. Pissy. Short.

Sometimes even at work.

“Hop on up, buddy,” Erica said again. “Come on: 1-2-3.”

It wouldn’t be unusual for her to have to say it twenty times, and effectively to count to 60. She had done it before. Many times. But this time, instead of fighting, Cohen stepped up onto the silver rung, which was there for just that purpose – she held his hand – and climbed into the high seat, made even higher by the thick cushion that the barber had put there to bring her son up to a height where he could work. He knew, that cushion told her. He knew. Knew he was going to be working on a little kid. How could anyone who knew a thing like that not be trusted? To do their best? To do the right thing? Always?

14

“I was so fucking naïve.”

15

“How do you want it?”

“Shorter, that’s for sure.” She wondered how often he heard this joke.

Often enough for him to feel like he didn’t even need to acknowledge it, apparently. “How do you want it cut, big guy?”

And that sealed it. Whatever misgivings she might have had about this man, about his attitude, his demeanor, vanished with those two little words: big guy. They spoke of a man who had a soul. Who perhaps loved children, maybe even had kids of his own. And if she’d had any left – misgivings, that is – deep seeded and stubborn, those too would have disappeared when her son answered: “Ummm, mohawk.”

And the barber threw his head back, and bellowed laughter. Deep and infectious. Lusty. Unselfconscious. The laugh of a lounge singer who’d had one too many whiskies. When he laughed, the lines around his eyes made him almost handsome. “I think your mom might have something to say about that!”

“If that’s what he wants,” she said.

He got this joke, too. “Oh-kay, mom…” As if he didn’t believe her. As if they’d known each other for years. As if they—

16

“I was completely disarmed, by this point.”

17

“Just a boy’s cut,” she told the barber.“Whatever that looks like to you will be fine.”

“Like this?” the man asked, pointing at his own head.

Erica smiled. “Sure,” she said. “Why not?” It would look at little different – who was she kidding, it would be a whole new aesthetic for the kid – but that was the point of getting haircuts, right? The barber wrapped a black cape roughly the size of a queen-sized blanket around Cohen’s shoulders, fastened it in back, and got started. Cautiously, at first – a snip-snip here, and a snip-snip there – slowly building up steam.

Cohen shut his eyes, and squenched his little face, as if he thought someone was about to throw an egg at him; and Erica braced for the inevitable freak-out. It didn’t come. So, after a moment, she cautiously took a seat in the empty stall next to them, and started fiddling with her phone. It was nice to take a break for a minute. To let go, and let someone else deal with him, at least for a while. The other stylist rang up her client, and disappeared into the breakroom. Erica snapped a picture of Cohen, and sent it to her husband. “Proof of life,” she put as the caption, no longer amused by the barber’s height, and frailty. Proof that he’s cooperating, was what she really meant. Her husband worried when she went out with Cohen all by herself. It sounded silly; but Cohen really could be so difficult, sometimes.

The reply came back right away: “Is he being good? Send me a video.”

18

“He was always doing that. Worrying about me. About us. Tying to protect us. Trying to keep us sane, and happy. He’s doing it now; even though I told him, specifically, not to come.”

Erica waved. “Hey, David…”

19

He’s being perfect, she decided she would send with the video. Because he was. Maybe she would write it in all caps. Cohen hadn’t even screamed when the guy clipped around his ears. His head was on a bit of a swivel, moving around, the guy had to keep holding it; but you expected that, when you were working with a boy his age.

Can’t sit still. Cohen never could.

She switched her camera over to video, and pressed record, still trying to be sneaky. She didn’t want to make the barber nervous. Didn’t know how he performed under pressure. Didn’t know if he was some freak who didn’t want to be filmed because he thought the government was watching him, or Jeff Bezos, or Mark Zuckerberg (or some wicked combination of all three). She might have asked, but that was a risk. He might actually say no.

And what she was doing was harmless.

She stopped her first take after seventeen seconds. She’d been moving the camera too much. She hated when she saw videos like that. They made her nauseous. And right towards the end, Cohen had moved his head, and the barber had told him to “Knock it off,” a little darkly.

That didn’t fit the narrative.

She tried again, bringing her phone up to her chest, and holding it with both hands to keep it steady. She centered Cohen, and pressed record. She figured would let it go for about thirty seconds. That wasn’t too long. You could send a video like that without any bother at all. But around fourteen seconds in, the kid moved, and the barber jerked his head back into position. Too rough. Her husband wouldn’t like that. She didn’t like it, either.

She would need to say something.

Her thumb drifted toward the red stop icon; but before it could get there, before she could stop the recording, or even look up from her phone, the scissors turned in the barber’s hand—

20

“I can’t picture it, for some reason” Erica said. “That little move. That little flick. The rest of it I see too much, all the time, but that part of it…”She shut her eyes. “I can’t make it make sense. It’s like a magic trick. I know it’s not. It’s something we do every day, a thousand times a day. Simple. I’ve tried watching myself, filming myself; but I can’t get the action to absorb into my brain. You know what I mean? But I could do it for you right now, easy, if I had a pencil, or a pen, or a pair of scissors. Just turn them around in my palm. That’s all…

“So fucking weird,” she finished, opening her eyes.

“Ma’am, I’ve asked you five times—”

“I know,” Erica said, cutting off the judge. “I know, your honor. I’m sorry.”

She drew a breath, hot and ragged, and continued. “The scissors turned in his fist, and he raised them up over his head, and he brought them down—

21

“Cohen!” Erica shouted, like she was mad at the kid. Like he was being bad. She had a lot of practice barking his name like that. Maybe that was why, when she opened her mouth, that was what came out. It wasn’t what she meant. She dropped her phone, and surged toward them. Surged was a perfect word for it. Like a wave. Like a bomb. Like lightning rushing up your cords to fry your circuits. An unstoppable force. The muscles in her arms and legs, back and torso, didn’t seem to have much do with it. She moved through that little distance faster than she would have ever believed. Faster than she had ever moved in her whole life.

Not fast enough.

Cohen’s arms and legs writhed under the black barber’s cape as he started to fight. So lively. Kicking – screaming. Erica was fiercely proud. Now you’ve got to deal with Cohen, you poor bastard! Did she really think this at the time? Or was that just her memory trying to set it all into neat little lines: this and then that; this and then that; and, oh yes, the analysis? She was never sure. See how you like it! See how you like it! Get him, Cohen! GET HIM! He could be so difficult. So stubborn. Such a little asshole, sometimes – but that was just because he was so strong. Willed. Armed and legged. All of it.

GET HIM!

“I said don’t move! I said don’t move!” the man was ranting – right up until Erica barreled into him. She shoved him against the wall – a distance of maybe four feet – like he was nothing. A leaf. A blade a grass. Weightless.

He bounced off, and came right back. Scissors raised above his head. A movie monster on a mission. His scream was just as lusty as his laugh. So full of everything: pain and rage, surprise, grief, health, sickness: “I SAID DON’T MOVE!”

22

“It’s not like I am a superhero, or anything. Or a boxer. Or an MMA fighter. I had never even really been in a fight. What happened was, my hand just flew up and swatted him away, like his head was a basketball that was flying at mine. All instinct. Lucky shot. I wanna say I threw a punch, but I think I actually hit him with my palm. There was a lot of force behind it. His momentum. Mine. I remember the way his jaw felt when—

23

She felt a snap, and thought: Good, I hope it’s broken, you twisted fuck. He went down, legs flying bonelessly out from underneath him, and he cracked his head, hard, on the linoleum floor.

The barber groaned.

“What’s going on? Is everything okay?” This had to be the other stylist, just now coming out of the breakroom. “Oh my God! Oh my—”

Too late, lady. I got this.

Erica fell on the man, raining blows. She had never been in a fight, but she had seen enough videos on the internet to know that the winner was usually the one who never stopped, no matter what. He brought his arms up, weakly, to try to defend himself – so Erica pinned them to the ground like grade school bully. They felt like little bird bones under her knees.

At some point, she got an idea: I could crush his windpipe. That would ruin his day. She wasn’t sure if this would kill him or not, but right then she didn’t care. I’m probably gonna get arrested, anyway. Might as well get my point across. She tried – bringing her palm down again and again, putting all her weight behind it – but his chin kept getting in her way. So, maybe that was what broke his jaw, ultimately.

That’s enough, part of her thought. But another part knew that it would never be. Knew that she would fight this man for the rest of her life. Forever. For always. Until the end of everything. Right there. Right then. She would never stop.

But eventually, someone did pull her off of the guy. Too strong to be the other stylist. It was the first cop on the scene, though she wasn’t able to process that information at the time.

Erica fought him, too.

“It’s okay. It’s okay. Stop,” the cop kept saying. “Listen to me, it’s okay. Stop.”

24

“Hold on,” the man’s attorney broke in. “I think you’re leaving something out.”

“Your honor!” the attorney for Erica’s side was scandalized.

“Don’t you think the jury has a right to hear, from her, how she plucked out my client’s eye? How she did it? What she used? What state my client was in at the time? If we’re gonna sit here all day, and let her work the jury, we can at least have her tell the whole story, can’t we?”

The judge was irritated. “Counsel will approach the bench.”

But Erica looked at him there, the former barber, with his little eyepatch, and decided she wasn’t bothered at all. “I used my thumb, actually,” she told the jury. “And it was more like a scoop than a pluck.” She tried not to smile. A smile would be inappropriate. “Like a little pop.” She popped her lips. Her attorney was trying to get her to shut up, but she went on: “I thought it wouldn’t work, you know? At first. Because I don’t have long fingernails.” She showed them. “But it worked just fine. Came right out. No problem. I think he might have been knocked out, by that point; but, boy, that woke him up. And he screamed. That had to be what brought the officer in off the street…” The judge was bringing her gavel down again and again, so Erica paused just long enough for the court to silence. What she said next earned her a look from her attorney. “They always scream so loud, don’t they? The crazies…”

25

“Listen. Listen to me.” Eventually she would. Not now. Not yet. “Stop. Please. This isn’t helping.” He was right, though. This man. Whoever he was. He smelled like he was sweating Kung Pow Chicken, but he was right.

And Erica suddenly remembered what she’d forgotten.

“Cohen!” He would run to her now, and she would hug him. Cohen gave the best hugs. “Cohen!” Where was he? She couldn’t find him. The room was too huge all of a sudden, too full of screams, too full of people. A vast ballroom in a fading strip-mall. “Cohen!” He would come to her. He had to. How could he not? She was his mother.“Coooohennnn!”

“Over here.” A woman’s voice. The stylist.

As Erica moved in her direction, she tried not to look at all the blood. The blood was meaningless. There was blood in every little boy and girl. Bloody knees, bloody noses. Blood at the doctor, when they pricked their fingers. Blood blooming into every bandage. Blood in every operating room. There was blood in men and women, too. Blood in all the birds and fish. Blood in cats. Blood in dogs. Blood in everything that moved.

But Cohen didn’t.

Erica shoved the woman out of the way, and scooped him up. “Cohen!” she barked like she was angry. Had that been the last thing that he heard? Had he thought his mom was mad at him, because of what that man did? She spoke softer. “Cohen…” Startle awake. Kick. Fight. He would do it. She was sure. Her son was so lively. So difficult. Cohen never sat still. But the kid was little bird bones, all at awkward angles. “COHEN!” Erica bellowed, shaking him. “Mom’s not mad! Please…”

26

“Is there anything else?” Her attorney handed her a tissue. With poor grace. He was still mad at her. For him this was just a trial, a job. He wanted to win. Not because he really cared, but to further his career. Life in prison for this man, this monster, would look good on his resume.

Erica thought about it. She might have told them how she had prayed. Asked God to put it back. Blood in all the birds and fish; but none in her Cohen. Not anymore. Wake me up! Wake me up! she demanded, but no one had been able to. She might have told them how she felt relieved, sometimes. Actually relieved that she didn’t have to deal with her son, who could be so difficult. No more having to hold him down at the doctor, as he fought and squealed like a captured boar. No more dragging him out in public, the way he’d forced her to drag him to his own murder. No more gun to her back, the kid’s willingness to flip the fuck out at any instant.

She might have asked them what that said about her.

But she already knew.

So she said: “That’s all I’ve got…” She looked at him then, the former barber. Sitting there in his tiny suit. He’d put on a little weight, but not enough to make him look healthy. Eye down. Face impassive. “I hope you get the help that you need,” Erica told him.

Another little jump from her attorney. Barely perceptible.

The defense then got to cross-examine her. Erica didn’t mind. She had lived through worse things, after all, and the facts were undeniable. What happened at the barber shop was not in dispute. In addition to her video, which had caught the stabbing itself, the shop had been wired with security cameras, so it was all on tape.

The only part that really mattered was: “So, what do you think should happen next?”

“I don’t know,” Erica lied.

“You said you hoped my client got help.”

“I do.”

“Do you think he needs it?” The barber’s attorney had just wrapped up a monolog about his supposed mental illnesses. Health problems. His horrible life. How all that had caused him to have a break – just a tiny, little break – from sanity, from sense, and therefore from responsibility.

“I don’t know.” This time, she was telling the truth. “I’m not a doctor.”

“Neither am I.” He left it open to imply that none of them were, here in this room. Except, of course, his expert witnesses. “That’s all I need, ma’am. Thank you.”

The trial went on for another couple of days, and in the end, the jury decided that they thought the guy needed help, too. He would be confined in a mental health facility. Not a prison. Erica tried not smile, as they handed down the sentence.

A smile would be inappropriate.

She hurried from the courtroom; dodging questions from the peanut gallery; ignoring David, and most of all her former attorney. The District’s attorney, Erica reminded herself. He had never been hers. Not ever. Not once.

She had meant to cross the street to the parking garage, when she got outside; but decided she needed to take a walk, instead. “I won,” she said when she was sure she had thrown off all her tails. Reporters looking for a react. David looking for comfort.

She had none to give.

Erica only had her own. “I won. I won,” she kept repeating to no one in particular under her breath. Just another crazy talking to herself in the park. If they had sent him to prison, he would have stayed in there for the rest of his life. That was what the DA wanted; but it was unacceptable. They would have never let him out.

This way, they probably would.

“And when they do, I’ll be ready.” She would find out where they were keeping him. Move there. Take a job. Maybe David would join her, eventually. Maybe not. Probably it would be better if he didn’t. She wasn’t sure he would understand. Wasn’t sure it was really helpful. Erica knew that it wouldn’t bring him back. Their son. Knew it wouldn’t wake her up from this nightmare. No more embarrassing trips to the doctor – but no more seeing the kid smile, either. Exclaim over a toy. Laugh at the TV, or one of David’s stupid jokes. No more hugs. Cohen gave the best hugs… And she was aware she might be kidding herself, might be wrong – about him, about the justice system – but she would move there, anyway, and she would wait. Wait until he was well enough to know what was happening to him.

No matter how long it took. She had time.

A line by Walt Whitman occurred to her. She’d had to write a paper about his life in Eighth grade; and apparently she still remembered it. It came to her suddenly, bright as fresh blood on a linoleum floor. With a little editing it seemed to fit: “I am thirty-seven years old, and in perfect health,” Erica whispered. “And I promise to wait until I die. Waitand watch. And when they do let him out…” She would cut him down like grass.

And maybe scoop out that other eye, just for the hell of it.

Erica smiled.

Alex Atkinson is a Writing and Linguistics major at Georgia Southern University with short stories in Crack the Spine’s The Year Anthology 2019; Running Wild Anthology of Stories, Volume 4; and Volume Three of Fearsome Critters Journal. For inquiries, he can be reached at alex@accesscms.com.

Stephen M. FeldmanAbortion Provokes

Abortion provokes, but Professor Frenchy Shaw never expected this.

“Let’s try again, Mr. Vogler. What do you think of the Court’s reasoning in Roe v. Wade?” Frenchy gazed from the lectern up and across the amphitheater, eight rows of tiered seats. The walls were white, the carpet brown. The bearded Vogler sat in the last row on the left.

“I already said I pass.” Vogler peered out from under a green John Deere baseball cap.

“Everyone in here knows I don’t allow passing in Constitutional Law.”

Vogler whispered to the student sitting to his right, Mr. Jones, who snickered.

A clunk vibrated from the ceiling, and the air conditioning switched on, blowing cool air at Frenchy’s back. She inched her blue blazer higher on her neck. “I’m wondering about the right of privacy the Court found in the Fourteenth Amendment.” She clicked the Power Point remote, and a slide displayed the constitutional provision. “Does that right encompass a woman’s interest in choosing whether to have an abortion?”

“You mean that Fourteenth Amendment?” Vogler pointed to the nearest overhead screen. A few students chuckled.

“That’s the one.”

“Reading the text,” he said, “there’s the Equal Protection clause. And a Due Process clause. But no, I don’t see any right of privacy mentioned in it.”

“Interesting point, Mr. Vogler.” She slipped her shoulder-length black hair, thick and frizzy, behind her ear. It popped back out. “So you’re a textualist when it comes to constitutional interpretation?”

“I read the text of the Constitution, if that’s what you mean.”

Jones, on Vogler’s right, snickered again, as did the other three men in their clique. They sat together in the back row and acted like high schoolers, whispering and laughing. Frenchy wouldn’t be surprised if one were to shoot a spit ball.

Vogler wanted to challenge Frenchy, as had many other students—usually men. She didn’t enjoy these classroom conflicts. She preferred to think of herself and the students as colleagues working together to understand the materials.

Frenchy stepped back, away from the lectern, while starting to cross her arms. But she stopped, not wanting to appear weak or closed to student input—however ridiculous or disrespectful. She returned to the lectern and grasped its edges as if behind a steering wheel, relaxed and in control, rounding a fat, lazy curve. “Can anybody respond to Mr. Vogler’s argument? Look again at the Fourteenth Amendment language.”

None of the ninety-five students responded.

“Is there no constitutional right of privacy because it isn’t explicitly delineated in the Fourteenth Amendment?” Two women raised their hands to half-mast. “Ms. Warren?” Frenchy nodded at the woman in the middle of the front row.

“I’m not positive, Professor. But I think the Court found the right implied in the Due Process clause.”

“Thank you.” Frenchy looked back to her left and up to the top row. “What do you think, Mr. Vogler? An implied rather than an express right.”

He sat up straighter. “If a pregnant mother has an implied constitutional right of privacy, then her unborn child does too.”

Frenchy lifted her water bottle from the lectern, flipped open its spout, and sipped. Icy cold. “Let’s suppose a world-famous virtuoso violinist is suffering from a life-threatening blood disease.” She looked up and left. “Are you with me, Mr. Vogler?”

He squinted at Frenchy.

“Good,” Frenchy said, taking another sip and snapping the bottle closed. “This violinist has a rare blood type, and just your luck, you’re one of the few individuals with the same type. In fact, only your blood can save the life of our virtuoso. The problem is that you must remain tethered to him for the next nine months, having your blood slowly but constantly pumped into his veins. For at least the first couple of months, you’ll feel sick. Over the nine months, you’ll gain around thirty-five pounds. And you might never return to your prior body weight and shape.”

Vogler hunched his shoulders and pulled his cap lower.

“Should you have a legal duty to sacrifice your blood for the violinist?”

“I don’t know,” he said.

“Does the law ever force a man to give a blood transfusion for the sake of another’s well-being?”

Vogler didn’t respond. The air conditioner clunked off, the air stopped blowing, and a disquieting silence settled on the room.

Jones, Vogler’s clean-shaven neighbor, shook his head and said, “This is ridiculous. It doesn’t make any sense.”

“Yes, Mr. Jones?” Frenchy said. “Please explain.”

“You can try to dress this up with hypothetical fantasies any way you want.” Jones pushed his wire-rimmed glasses higher on his nose. “But we all know what you’re talking about.”

I’d be thrilled if you understood what I’m talking about, Frenchy thought. But she forced a smile. Her job was to teach, not use Socratic questioning as a weapon. “What’s that, Mr. Jones?”

“Murder.” Several students groaned while others nodded in agreement. “Abortion is murder—”

“Thank you, Mr. Jones. That’s—”

“It’s murder of the grossest and cruelest kind!”

“I said that’s enough.”

Frenchy pressed her eyes closed, then opened them. Other students were yelling at Jones, some encouraging and some rebuking him. He raged on, “The innocent babies are either dismembered inside the mother’s womb or torn to shreds by vacuum suction.”

“Oh, gross,” a woman called.

Frenchy, her face hot, marched up the aisle toward the back row. The farther she advanced, the quieter the room grew, except for Jones. “The babies are then thrown into a dumpster. Their souls—”

“Mr. Jones! Either you stop, or you leave.” Frenchy halted at the penultimate row. Jones stared at her. The room silent. “Do you understand?”

“Yes.” He turned toward Vogler, who grinned and fist-bumped him.

Frenchy’s body trembled as she returned to the front of the room. She grasped the lectern to steady herself. “All constitutional cases,” she said, “are partly political.”

Jones snorted loudly.

“We can express our politics,” Frenchy continued, “but within the language of the law. As the justices themselves do.”

She glared in Jones’s direction, then looked around the room. “There’s a difference between partisan posturing and politics expressed through legal arguments. Does everybody understand?”

Nobody said a word.

“Mr. Jones, do you understand?”

He nodded.

“What’s that?” she demanded. “I expect you to apologize to the class.”

“You’re joking, right?”

Frenchy cemented her face into a scowl. “Do I look like I’m joking?”

“Sorry,” he muttered.

“What?”

“I’m sorry.”

Frenchy checked the clock. Class should have ended two minutes earlier. “Okay,” she said, “that’s it for today.”

The class erupted into a cacophony of books slamming, notebook computers clacking closed, and students standing and talking.

Frenchy looked down. Had she been unfair to demand Jones’s apology? If she allowed students to proselytize, class would devolve into a face-off between Fox News and MSNBC. She needed to take a stand, but what was the point of humiliating him?

Frenchy gathered up her materials while berating herself for losing control of the classroom. Cradling her papers and tome-sized book in her arms, she hooked a finger through her water bottle, then turned to leave. Ms. Warren, the woman in the front row, stopped her but didn’t speak.

Frenchy smiled. “Ms. Warren, that was a good answer you gave today.”

“Thank you, Professor.” Warren looked past Frenchy’s shoulder, toward the blank blackboard.

“Do you have a question?” Frenchy asked.

“Sorry. I just wanted to say I appreciated how you stood up to Mr. Vogler.”

Stephen M. Feldman is the Housel/Arnold Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of Wyoming (sfeldman@uwyo.edu). He has been an NEH Fellow and a Visiting Scholar at Harvard Law School. Professor Feldman has published a short story in the J.J. Outre Review as well as non-fiction books with Oxford, Palgrave-Macmillan, Chicago, and NYU presses. The idea for the protagonist’s classroom hypothetical involving abortion and the violinist is derived from Judith Jarvis Thomson, A Defense of Abortion, 1 Philosophy & Public Affairs 47 (1971). Professor Feldman is currently working on a novel, The Family Law, and a nonfiction book on court-packing.

Joseph Charles MollicaThe Always Wet World

Leaking again, the upstairs people text me. The biggest bucket is out. Grandmother looks cold and needs the extra blanket. I retrieve it from the pile under the tarp and cover her legs to stop the wet air that gets between them. On it, I text back. She has lost her will to speak, but at one time she was good value on the subject of the rain. She called the rain blood and said the Arcs they were manufacturing in secret bunkers and packing with pretty people and animals and vaccines were just cheap knockoffs that would never convince the blood to stop. Grandmother watched the news and gleaned little bits of information from my phone conversations, but I couldn’t say for sure that she understood what was happening. Before she stopped talking, she told me she was no longer concerned with the after-life. She’d lived in lower east side tenements, survived WWII by recuperating her investment in the form of the soldier to whom she was engaged, forty years plus of Catholic-house-wife drudgery, four good-looking and thus quite insufferable children – my dead mother included – and the attendant abuses perpetrated by these siblings upon her sensitive and aching heart, a hundred thousand migraines, bunions that needed surgery twenty years ago, the protracted death of her youngest grandson, Al, the knee and the hip replacement, and now this, the blood. The doctors told her the rain was good for her. She complained about them (silently) because they had a different name for the new times – they called it the umbrella world, or the always wet world. I know she is watching me check my phone, moving the buckets under the trouble-spots. You imbecile, I can hear her thinking. Just put on a new roof.

Joseph Charles Mollica was born and raised in Queens, NY. He is a teacher, a former newspaper reporter, and a graduate of the New School MFA program. His short fiction has appeared online. He lives with his wife and daughter in Sag Harbor, NY. Reach him here: Josephcharlesmollica@gmail.com.

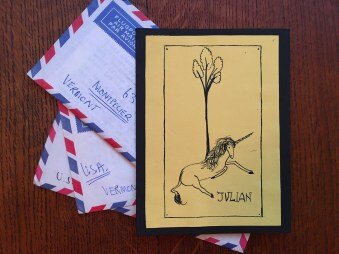

Mark HallTalismans Against Our Next Meeting: Search for a Mysterious Lost Love

Days before his death, from his hospice bed, my friend Julian made a handwritten change to his will, entrusting me with his personal papers—manuscripts, photos, and correspondence. Among them, Julian directed me to a cache of faded love letters, tucked inside a small wooden box, buried beneath a jumble of papers in the drawer of a dust-covered planter’s desk. After his death, I became captured by these letters, searching them for a way to know Julian, to bring him back to life. In these letters, Julian is very much alive, but a person I did not recognize. In the twenty years I knew him, Julian never spoke of Michael, the author of these letters. In fact, he never spoke of any love relationship. What made him trust these letters to me? What window might they open onto Julian’s life?

In his first letter, Michael writes to Julian:

I sit at a worm-eaten desk by flapping brocade curtains and realize, Julian my dear, that I love you. It is no use sending you vague insinuations or philosophic hints (which I am incapable of anyway). I hope I know you well enough to believe what you told me. . . . [A]t the time . . . I was living so intensely, so quickly (and so much without sleep!) that I was aware only of the joy, only that suddenly everything was right. . . . But now, suddenly without you and indeed without anyone—for you know there is no one in Wien—I realize Julian that you are . . . I am sorry I am getting corny . . . I’ll say only that I love you and that everything I said was true and upon reconsideration. . . . My syntax is bogged down—I shall go to bed now and very likely destroy this letter tomorrow. But for tonight—I shall think only of you . . . and go to sleep more convinced than ever that I am in love for the first time.

In love for the first time. Michael’s letter sent me right back to that same moment in my own life. From the first, I was drawn in by his gift for description, captivated by the intensity of his feelings, his candor, his unabashed affection. Unlike so many men I have known, Michael is eager to express his feelings, both passionate and self-aware.

Having come of age in the mid 1980s, as AIDS—in those early days, a terrifying mystery—ravaged the gay community, I was reminded of how hesitant and afraid I had been as a young man. Yet here was Michael, only 21 years old, I learned from another letter, proclaiming his love for Julian with such boldness and confidence, which I could never have imagined at his age. Unfettered by fear, this love from a time before sex could kill was foreign to me, yet rich with possibility. While I identified with Michael, at the same time, I could also imagine myself in Julian, bolstered by Michael’s frequent reassurances:

The time element is not so important to me, as I told you I have known your prototype since I was thirteen but never expected to actually meet you (did you realize during those ten years that someone was seeking you?). Having found you I have no intention of losing you. I never cease fantasizing about our next meeting, whether it is for a week, a summer, or a year. I shall try to teach you the trust that comes so easily to me, when you are here my faithfulness will not be in fulfillment of a demand, but a consequence of loving. In letters I can only hope to indicate the tenacity of my affection: the proof will come later. You need not tell me how difficult it must be to accept noble words and rosy vision; you make love rather shyly, you know. It is one of your charms, but I shall be glad to see the intensity born of confidence.

Some readers may find Michael’s letters over-wrought, “corny,” as he puts it, but I find them charming, smart, funny. While I lacked Michael’s fearlessness, he reminds me, at times, of myself at his age. Baffled by casual, brief encounters, I fell madly in love with every boy I met, then wrote them fervid love letters, like Michael’s, and so, I understood the intensity of his attachment to Julian. Eager to learn more, I read on.

* * *

My back to the door, I was slow to feel a pair of eyes on my neck. Taking a break from a long afternoon of grading papers, as dusk fell and shadows lengthened across the quad, I gazed out my office window at the small college in the Carolina Piedmont where I taught English. A rustle of clothing snapped me back to attention. When I turned, there in the dim light stood a dark figure, dressed all in black, including a long, elegant herringbone cape. Hanging from a shoulder, clutched in a bone-white hand, was an old-fashioned black patent leather purse, like one my grandmother might have carried in the 1950s. In the other hand was a cigarette, clasped in a glossy, black Bakelite holder. With long, dark hair, dyed an unnatural shade of walnut, this mysterious visitor’s gender was not immediately apparent. Then, in an unexpected crisp British accent, like a stern English nanny, Julian introduced himself.

He had once taught French and German at the college, he explained. He’d learned from a mutual friend that I owned a pickup truck, and wondered if I might be available to transport his book collection to the college library. Now that he was retired, he planned to donate his vast library, and then visit his books on campus, where he spent his days studying Russian.

This was my first pickup truck. I’d only had it a few months, but already I understood that owning a truck came with certain obligations. A truck was a magnet for anyone with something to move, and its owner was expected to be obliging, especially in a small Southern mill town like Greenwood.

At the time, my students were reading Pat Conroy’s The Prince of Tides. A recent class discussion had focused on a minor character, Mr. Fruit, as in “fruitcake,” or crazy person. The lovable, crazy Mr. Fruit directs traffic at an intersection in Conroy’s fictional town of Colleton. Conroy’s narrator remarks that one can take the measure of town by the way its people treat the town eccentrics like Mr. Fruit. On first meeting, I recognized that Julian was one of Greenwood’s Mr. Fruits, a real character. With scant opportunities to haul anything more than a stack student papers, I was pleased to offer him my assistance. We made arrangements to meet on Saturday. Following his directions, I recognized Julian’s house right away, an old, tumbledown mansion on Main Street, not far from the Uptown Square. Tucked back from the road, screened by an impenetrable thicket of sweet viburnum, his was the house I called “Boo Radley’s Place.” Cloaked in the deep shade of overgrown sasanquas, with its knee-high grass, the dilapidated structure betrayed no indication that it might be inhabited.

At the appointed time, Julian invited me in through the kitchen. For several minutes, I struggled to adjust to the dim light inside. Heavy, dark drapes covered the windows. All the walls and even the ceilings were painted the same dark pea green. The house was like a cave. Its rooms were piled high with boxes, books, newspapers, furniture, and clothing. In one upstairs bedroom, I counted nineteen rocking chairs of various styles and designs. In another, dozens of lamps of assorted description. It was a hoarder’s paradise, like one of those storage lockers you see on TV, packed to the rafters, with narrow paths for navigating. With every corner I turned, I felt more lost and claustrophobic. Julian, however, appeared unfazed. He led me to a rich magnolia-paneled library filled with books, then pointed to an assortment of liquor store boxes to pack them up.

While I worked, Julian talked. Though reared in the deep South, Julian spoke the Queen’s English. His British accent, which would have seemed an affectation on anyone else, was, I came to understand, utterly authentic on Julian. It had seeped deep into the bone. In conversation he switched seamlessly from English to German, French, Italian, Russian. He expected his listener to keep up.

In addition to teaching at the local college, Julian had taught English decades earlier at the Berlitz School in Vienna, Austria. This after years of studying music. A child piano prodigy, Julian had travelled as a teen from South Carolina to study at the Royal Academy of Music in London, then later to Paris to the Académie de Piano with the famous Marguerite Long. But a mental breakdown, his “loo-loo,” as Julian called it, had put an end to his career as a pianist.

As he talked, Julian fingered a worn, black prayer rope. In time, I would learn that Julian was never without this prayer rope, worrying it constantly, a nervous tic that had found its purpose. Julian was deeply religious, devoted to the Russian Orthodox Church. His cave-like dwelling was a monk’s cell, its walls crowded with dour icons.

Never without his dead mother’s black patent leather purse, his cigarette holder, and his prayer rope, in the weeks that followed my help with the books, Julian found new reasons to call on my pickup truck and me. I made countless trips to local charities, hauling all manner to things out of his house, among them, a truckload of his mother’s shoes, most of them decades old, never worn, still in their dusty, faded boxes.

* * *

Michael’s letters raised so many questions: How and where had he and Julian met? What had sparked their relationship–and what had ended it? I searched his letters for answers. In one, looking forward to their reunion, Michael recounts how he and Julian met:

I am delighted to read that I become more important to you . . . but please don’t allow me to alter in your fantasy to someone I am not. It is easy enough to do this with people whom we see from day to day, and almost impossible to avoid in the case of those separated by an entire ocean.

I certainly do agree with your idea of totality. I am not sure what your sexual vorstellungen have been, but mine, thanks to my eccentric upbringing, have always been rather healthy. I could quite cheerfully enjoy sex without any other features, just as I could love someone in a basically platonic way. You, of course, are one of the first people with whom both were consolidated, reciprocated and consummated. And it has made anything else seem inadequate and a bit depressing. But unlike yourself, it has not been nearly so difficult for me to express this sort of family affection, love, friendship, and desire all rolled into one, which I feel for you. Everything was so perfectly natural and almost inevitable. Of course, it all happened in a marvelously hoch bürgerlich way—I mean in that I did not pick you up on the street, say, or in one of those mass meeting places called bars. The order of our friendship could scarcely have been slighted by Emily Post. I even vaguely remember that with true Victorian spirit I asked you if I might kiss you. This, of course, is all very nice but it doesn’t really matter. If I had met you while on a gang rape, a banana boat cruise, a bar mitzvah, or a Sunday school outing it still would have happened. I am so lucky not to need “emotional camouflage” and that you don’t, either. It would be rather a pity if either of us believed a) he was or ought to be completely straight b) affection and/or dependence is a sign of weakness. But as neither apply to me, and neither apply ich nehme an, to you, we can rejoice in knowing each other, as you say, totally. So if I visit you in a few months you may be prepared for Comradeship, Understanding, Long Talks, Scintillating Wit, Profound Discussion, and (if I am not mistaken, a fortnight has 14 nights, count them, four-teen) S*X.

Through his letters, I came to know Michael, as Julian must have done. His self-possession made me wish to know him better. I imagined myself the recipient of such ardent love letters. To me, Michael’s devotion was electric. At the same time, through Michael’s eyes, a very different Julian than the one I had known began to take shape.

* * *

A few months after he first visited my campus office, Julian traveled to London to celebrate Easter at a Russian Orthodox Church there, his church, as he described it. While he was away, he asked me to look after his house for him. He hoped I would stay the night, but I never did. The pea-green walls and ceilings, the heavy drapes, the religious icons, the dim lights, it was all too spooky for me. Added to this, one evening, while Julian instructed me on how to make an authentic Hungarian goulash, I startled as a black racer slithered under the refrigerator. With a wooden spoon, Julian airily waved away my concern, then topped off his glass of wine.

During his absence, late at night, I’d sometimes take friends over, after a few drinks, to tour Julian’s house. We’d peer into closets and riffle through drawers. The rambling structure was like a museum, a time capsule. Whatever entered, wherever it landed, remained. On a chair inside the front entrance was a worn satchel, dropped, as though someone had put it there on returning home from school that afternoon. Inside were a biology textbook and a neatly typed lab report, written by Julian’s mother, when she had been a Master’s student at Emory University in the 1930s. Open a chest of drawers, and inside you might find three dozen pairs of women’s white gloves, still wrapped, not in plastic, but its precursor, cellulose.

My favorite object in the house was a portrait of Julian as a young man, painted during his time in London. The artist, Alfons Purtscher, I learned after Julian’s death, was a prominent Austrian horse painter, an illustrator of children’s books. Indeed, the young Julian, dressed like an Edwardian schoolboy in a Merchant Ivory film, has a certain horsey look about him, a beautiful mane of glossy, chestnut hair.

* * *

In all there are nine postcards, two Christmas cards, and 32 letters, most written on thin sheets, folded inside pale blue AirMail envelopes, with their distinctive red and blue striped border. There are context clues, but ordering the letters with complete accuracy is unlikely. The postmarks are long-faded, impossible to decipher. Their sequence is further obscured because dates written inside are idiosyncratic, often vague: “Saturday,” “Monday Morning, Wien,” “Berg Bernstein, Midnight.” One envelope may contain multiple letters, composed over several days. My best guess is that they begin after a five-day affair in August 1969 and end with a Christmas card the following year. I have only the one-sided communication from Michael to Julian. Of this correspondence, Julian told me only that he hoped I would “do something,” as he put it, with the letters, something to honor the legacy of love they detail.

To decipher their narrative, I created a spreadsheet, numbered each letter, then set about cataloguing their contents, trying to discern the order, looking for significant patterns and themes, an arc to the story. Together, the letters are a window, albeit opaque and incomplete, into the past, into a friend who, only after his death, I longed to know better.

* * *

For all my assistance clearing out his house, Julian was generous, pushing this chair or that lamp on me to take home. Inertia, rather than attachment motivated Julian’s hoarding. He showed no interest in things. Julian’s mind was elsewhere, filled to the rafters, like his house, but with ideas—about language, literature, art, philosophy, religion. A self-described hermit, Julian was sociable, yet he kept mostly to himself. Highly educated, an accomplished pianist in his youth, having lived abroad as a young man, with mastery of a half dozen languages, Julian was out of place in the tiny mill town in South Carolina where he had grown up next door to Senator Strom Thurmond’s nephews. There Julian was one of Greenwood’s most conspicuous eccentrics. While he lived a life of voluntary solitude, Julian was obviously lonely. As we became better acquainted, he’d show up at my house at all hours of the day and night, always in search of a drink. Quickly, I learned that opening a bottle of wine was O.K., but whiskey turned Julian maudlin. Often, I was impatient with him. I avoided him. I was busy, a new teacher, in over my head, still finding my footing with a heavy course load. As often as not, I pretended not to be home when Julian came calling. When I moved to another state a few years after meeting him, I was relieved. Julian had become, increasingly, a burden. He would be easier at a distance, I thought. By phone, I could keep Julian at arm’s length.

* * *

As I read on, I learned that his father’s illness had prompted Julian to return to the U.S. soon after meeting Michael. His father’s death a short time later prevented Julian from returning to Vienna. In his letters, Michael is plagued by the separation. In spite of the distance—or perhaps because of it—Michael is eager to prove his faithfulness. In recounting a conversation with a friend who was contemplating ending a relationship of her own, Michael tells Julian:

She spoke of the inadequacy, indeed the grave danger of a correspondence. It is easy to allow the person to whom you are writing to assume fantastic proportions, she said, and easy to say things in a letter that stick in the mouth when the person is once again standing before one. . . . I do not do this with you, I don’t think, for I remember all your weaker points with stunning clarity and I was just as enchanted then as I am now. But don’t let it happen to you, Julian, for your psyche is more sensitive than mine and more prone to fantasy. Our relationship must be one between two human beings (flawed yet gorgeous as we are) and not an ephemeral correspondence between our ideal selves. I love you as a person not as an idea and I hope it is in this way that it is reciprocated. With the warts dear, with the warts.

No correspondence, however, could sew up the divide that separates these two lovers. Even so, Michael continues to write, to use his words to forge, as best he can, an authentic connection with Julian.

* * *

On first reading a few of these letters, I began to search in earnest for Michael. At the time of their meeting, Julian would have been 36 years old, Michael, 21. If he had been 21 in 1969, then in the year of Julian’s death, Michael would be only 66. He might still be alive. But with a common first and last name, Michael would be difficult to track down. I began compiling a list of details. Both Julian and Michael had taught at the Berlitz School. Perhaps they had met there. Several of Michael’s letters, he explains, were written while his students were taking exams. Michael might still be a teacher or professor. Perhaps he now taught at an Austrian university, or somewhere else in Europe. In his letters, Michael speaks of dual citizenship in both the U.S. and Great Britain. By now, he could be anywhere.

* * *